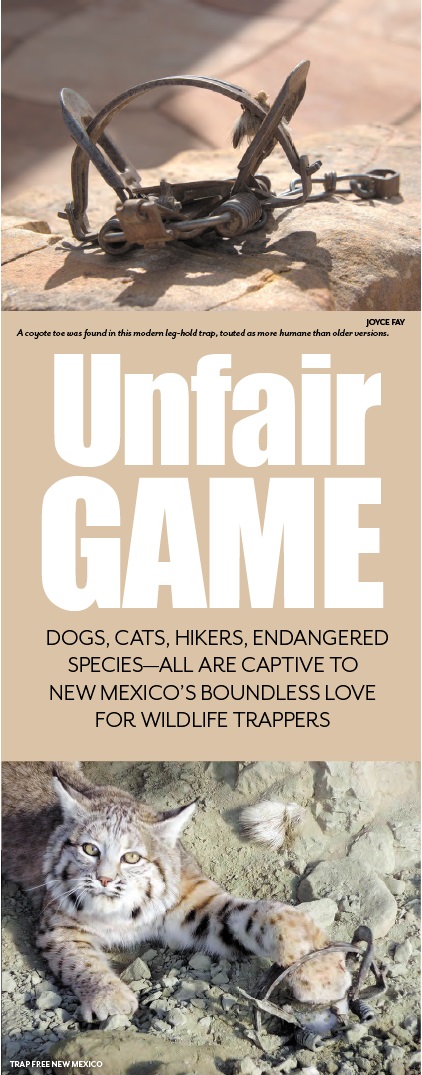

THE MOST STRIKING THING in stories about dogs caught in wildlife traps is the similarity of their humans’ reactions. Man or woman, rural or urban, their dog’s unearthly screams are a sound many say they will never forget—along with getting bitten while trying to free their animals. Many dogs have lost legs in traps; cats often fare worse because it takes so long for them to be found. Over the last ten years, fur trapping—which many people think of as a relic from the 1800s—has grown into a contentious issue on public lands in a state that does not limit how many traps can be set.

Bobcat is the most lucrative catch. Until about ten years ago, a pelt might fetch $80, according to Trap Free New Mexico spokeswoman Mary Katherine Ray. Today, depending on how thick and spotted the fur, a pelt might bring $800 to $2,000 at auction. Thanks to demand in China and Russia, even fox and coyote can fetch $20 to $40 to be used for trim, Ray said. While prices dipped a little during the recession, interest in trapping has not.

In New Mexico, thousands of traps lurk a short distance from National Forest, BLM, and state trails, many in popular hiking areas like the Gila and Lincoln national forests. Every year, more than 2,000 bobcats are trapped, according to New Mexico Department of Game & Fish data. Bobcat is the only “harvest” that is accurately known, since the pelts must be tagged to certify that they are not from an endangered species. What is not known is how many bobcats remain in the wild, since Game & Fish does not track the furbearer population, and all wildlife suffered heavy losses from wildfires in the last few years.

Trappers are not required to report any “non-target” animals they catch, and no agency counts the number of pets killed or injured. But casual lists like the one kept by Trap Free New Mexico, or the national group Born Free USA, send a chilling message to anyone who runs their dogs outdoors. So many pets have been mangled in traps that a number of hunting and outdoor groups have created YouTube videos showing how to free your dog, since many hikers are unable to do so alone. Studies have found that non-target animals make up two-thirds to three-quarters of the typical trapper’s catch.

Even in urban areas,

pets and people are not immune. In November 2013, a dog walked into a

trap off the Embudo Trail in the Sandia, just a quarter mile from the

trailhead at Indian School. The trapper claimed the popular trail

extension was exempt from the 25-yard buffer zone. Hikers have

encountered traps in Placitas, in Eldorado, and across Santa Fe and Taos

counties. In February 2013, a kitten lost part of a paw in an illegal

trap set near Rio Grande and Indian School roads.

For Mary Katherine Ray, two encounters with traps—including the

traumatic experience of finding a coyote in one on a Sierra Club

hike—transformed her politically. “The thought that someone could do

that to someone else changed my life,” she said of how it ended the

peaceful refuge she took in the outdoors.

Many people report being badly shaken by traps, even if their dog

escaped with life and limbs. Terry DuBois and the rest of the Mountain

Canine Corps practice search-and-rescue with their dogs in Los Alamos

County twice a week. Last January, her 12-year-old Heeler started

shrieking on a well-established trail on Forest Service land. Luckily,

one of her friends had seen the video on how to open a trap, and Jetta

escaped with a limp. But the experience led DuBois and others on the

corps—including another who had a dog trapped—to fight for a ban, which

they successfully passed in Los Alamos County last April.

At the state level, trapping is protected by the political might of

ranching and hunting groups. Though many hunters oppose hunting on

humane grounds, says Ray, “the hunting groups seem to feel like it might

be a slippery slope to banning hunting in general”— though nothing of

the kind has happened in Arizona or Colorado, which banned trapping in

the mid-1990s.

Hunters, in fact, register a strong presence on Trap Free New Mexico’s

list of victims with stories to tell, since they often range across

public lands with their dogs. Several recount coming across wild animals

caught in traps and shooting them to end their suffering, including one

who found an endangered species of rabbit that had nearly torn off both

paws. “I have to say it was the most satisfying thing I’ve done all

week,” the hunter wrote about shooting the rabbit and hurling the trap

down a mine shaft. “As a hunter myself, I find trappers and trapping

unconscionable.”

Last year, 1,831 people bought furbearer licenses in New Mexico, of

which maybe a quarter used them to hunt the target animals, according to

Ray. These include beaver, muskrat, fox, badger, raccoon, and bobcat,

whose seasons run anywhere from November to May. That leaves about 1,300

to 1,500 “fur harvesters” who use the license to trap. Since coyote and

skunk can be trapped anytime, traps are abundant year round.

Trappers are supposed to report to Game & Fish the target animals

they kill, but it’s nearly impossible to know if they do. Most set two

or three dozen traps, but some set hundreds. By law, traps must remain

25 yards from hiking trails and public roads, be marked with the

trapper’s identity, and be checked every 24 hours. In practice, traps

are rarely checked more than every few days, as trappers prefer to wait

until their catch has died of thirst, infection, gangrene, or predation.

“I feel like a prisoner in my own home” writes one hiker who lives in

Socorro County of a trapper who had taken over a nearby canyon. “It

takes him 6 hours to check all his traps—there must be hundreds of them

and he has been here for weeks already. It will probably be years before

I see a bobcat again.”

In searching the dozens of reports about pets being caught in traps,

we could not find a single case where the agency penalized a trapper for

violations. In fact, game wardens often failed to appear when called.

We were also not able to find a single case where the agency returned a

reporter’s call— including ours.

“They feel they can do what they want to do, and don’t have to answer

to the general public,” said Ray, adding that the situation had grown

worse under Gov. Susana Martinez.

This widespread perception that Game & Fish serves livestock and

hunting interests alone feeds the frustration of outdoor enthusiasts who

say a small minority is allowed to exploit a public resource to the

detriment and danger of everyone else. Trappers pay $20 for a license,

and are allowed to take and sell whatever they catch on public lands.

“The Game Commission is so slanted against us,” said Terry DuBois,

“and you’re not getting lay people on that board. If you look at the

people on Game & Fish, they’ve all been appointed by our governor,

and most of them represent ranching, hunting, and gun-type industries.”

In fact, the Game Commission—an appointed body that oversees the Game

& Fish department—has faced embarrassing accusations against its top

officials in recent years. Game Commission chairman Scott Bidegain

stepped down a year ago after reports of illegal cougar hunting on his

ranch, after he won a prize in a coyote-killing contest. In 2013, agency

director Jim Lane— known for his pro-hunting, anti-conservation

stance—resigned abruptly with the unanimous approval of the Game

Commission. In 2008, director Bruce Thompson resigned over allegations

of an illegal deer hunt. Meantime, the state’s population of black bear

and cougar appear to have fallen to dangerously low levels that are not

being monitored.

Once again this year, Rep. Bobby Gonzales of Taos will introduce a

bill at the state Legislature banning trapping on public lands. His last

attempt in 2013 died in committee in a vote mostly along party lines.

“Why individuals voted against it, I can’t answer for them,” Gonzales

said, adding that ranchers tend to support trapping because they see the

target animals as a nuisance.

Gonzales says he has constituents who have had dogs injured in traps,

and opposes the practice because it is cruel. “It’s a very antiquated

way of trying to catch animals,” he said. “And the suffering— you’d

think today you’d have more understanding.” He said he saw such an

outpouring of support after his 2013 bill, he is certain that a ban

would pass if the issue were put to voters. That option is not

available to New Mexicans, however, as it was in Arizona and Colorado.

According to a 2005 poll by Research and Polling Inc., 63 percent of

New Mexico voters support a ban on leghold, snare, and lethal traps on

public lands. In 2011, more than 12,000 comments were submitted to Game

& Fish advocating a ban, after the Game Commission voted unanimously

to lift a temporary ban on trapping in the Mexican Gray Wolf Recovery

area. Some 14 endangered Mexican Gray Wolves (out of a population of 50

at the time) had been trapped, several of them requiring amputation.

Incensed that the agency had ignored public sentiment, a coalition of

conservation and animal advocacy groups held a People’s Forum Panel on

the issue in September 2011, and reported that 90 percent of comments it

received ran in favor of a ban.

Of course, trappers are unlikely to comment on such an issue, being

well aware of public sentiment. We reached out to Tom McDowell,

president of the New Mexico Trappers Association (NMTA), but he was out

of cell-phone range for at least a week on a trapping expedition,

“helping a rancher,” according to his family.

Terry DuBois confirmed that those who oppose a ban are concerned not

only with protecting the income that comes from an occasional bobcat

catch. “They feel like trapping is a constitutional right, and having it

taken away is a violation of their rights and privileges as American

citizens,” she said. “They feel like the animals are theirs for the

taking, and it’s their right to do with them as they please.”

The state of New Mexico, based on all available evidence, agrees with them.

For more information

Trap Free New Mexico: www.trapfreenm.org

People’s Forum Panel on New Mexico

Public Lands Trapping:

www.nmtrappingforumpanel.org

Born Free USA: www.bornfreeusa.org