Excerpted from a study published in The New Inquiry and reprinted by permission of the author.

THE CENTERPIECE of the documentary Blackfish is the gruesome death of Sea- World trainer Dawn Brancheau, killed in 2010 by Tilikum, a 6-ton bull orca. Dawn’s autopsy report dryly states that the 40-year-old suffered numerous abrasions, dislocations, a broken back and jaw, hemorrhaging at multiple sites, and death by suffocation. Her right arm was missing, and she was scalped. The time of death was some 30 minutes before Tilikum relinquished Dawn’s mutilated body.

Dawn was one of SeaWorld’s most experienced and respected trainers, and she had a reputation for following safety protocols. Working with whales was a childhood dream; Dawn was also SeaWorld’s public face, appearing on commercials, billboards, and murals. “She was beautiful, blonde, athletic, friendly,” one colleague remembers. “She captured what it means to be a SeaWorld trainer.”

Blackfish is spellbinding. Accounts of this orca attack and others seems to indisputably prove that the whales are stressed, sickly, and agitated, and that SeaWorld cares not a whit. Of course, none of this is much of a surprise. The film’s central argument would seem self-evident: A business that profits from suffering prefers to conceal it.

No, the precise horror of Blackfish is not that Tilikum killed, but that Tilikum killed his trainer, and in such a single-minded, grisly fashion. Dawn fed and cared for Tilikum, touched and spoke with him constantly, understood better than anyone his moods and rhythms. Blackfish is about animal captivity and orca sentience, but the story of Dawn is also a tragic chapter in an ongoing history of wild animals and their female muses. Dawn’s fate is a variation on a well-established pattern: Attractive, single, childless women have long been coupled with exotic animals. Gentle women and wild animals are linked in myth and fable, fashion and pornography, pulp art and fine art. Crudely stated, men hunt wild animals, and women cuddle them.

Zoologic Madonnas

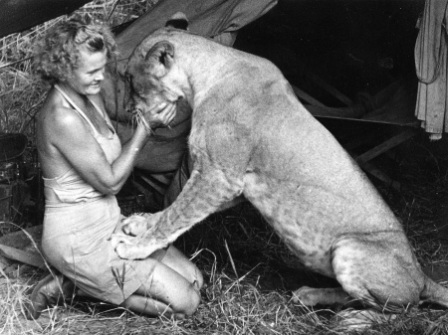

A matrilineage of media-friendly animal shamans emerged in the 1930s. Nearly all of the wild animals that Westerners are most fascinated with made their public debut beside a young woman. The first photos of a live panda were images of baby Su-Lin nestled in the arms of 1930s socialite Ruth Harkness. The first close-up images of chimpanzees in the wild were those of a chimp reaching to touch long-legged Jane Goodall. There was Margaret Howe hugging dolphin Peter, the zoologist Dian Fossey, of Gorillas in the Mist fame, coyly lending her pen to gorilla Peanuts, and Joy Adamson nuzzling the lion Elsa, whom she raised as a cub and rehabilitated to the as examples of self-destructive fanaticism; a more generous interpretation finds in them evidence of a radical form of interspecies love.

In

Dawn’s case, intimacy did not protect her from Tilikum; it provoked

him. Tilikum grabbed hold of Dawn’s body during a part of the

performance known as the “relationship session,” a time at the end of

the show for whale and trainer to decompress and reconnect. The pair was

lying side by side in shallow water, bodies parallel. Immediately

before the attack, Dawn was tenderly stroking Tilikum and gazing into

his eyes.

Dawn’s dilemma was the product of a seemingly insatiable public

appetite for images of women and their animals. Animal-woman encounters

are the subject of TV specials, Hollywood films, and best-selling books.

The animals vary, but the tropes remain consistent: The creature is

either powerful and large or cute and vulnerable, and the woman always

young and pretty. When the animal-woman encounter is not rehashing

Beauty and the Beast, it’s mimicking the poses of euphoric mothers and

infants, the baby replaced by a cuddly bundle of fur.

The iconic status of these encounters flattens the intensity of the

relationships they represent. A woman cuddling a wild animal suggests

many things to many people, but behind all that is a real woman and a

real animal who have developed an exquisite and unorthodox bond. The

texture of the relationship is difficult for outsiders to comprehend; it

has none of the physical likeness of an intimate human relationship,

but all of the nuance and depth. The women’s letters, biographies, and

journals show that while they encountered their animals as scientists or

trainers or caretakers, they eventually built powerful, all-consuming

relationships in which the animal made demands, and the human recognized

those demands as being equally legitimate as her own.

A grief beyond measure

Dian

Fossey’s work with mountain gorillas in Rwanda indicates she did not

assume a categorical difference between human and animal. Having flunked

veterinary school, Dian was working with disabled children in 1963 when

she took out a loan to pay for a safari that was everything she’d

hoped. When she spied the “patent leather faces and deep brown eyes” of

adult gorillas in the wild, her fate was sealed. With the support of Dr.

Louis Leakey and the National Geographic Foundation, she permanently

moved in 1966 to the bush of Congo and then Rwanda, and devoted her life

to the study and survival of mountain gorillas.

There are dozens of examples of Dian’s bond to her gorilla community,

but none is more poignant than her attempts to cauterize her grief over

the death of Digit, her favorite gorilla. Digit and Dian had known each

other over a decade and she claimed Digit knew her thoughts. In 1977,

Digit’s body was found laying in a pool of diarrhea, decapitated and

riddled with spear holes, missing his feet and hands. He’d been brutally

murdered and spent his last moments in terror. Dian was heartbroken. A

page of her diary written years after his death contains nothing but his

name, repeated ad infinitum: “Digit. Digit. Digit. Digit.”

Dian mourned Digit by avenging his murder. She captured and hogtied

Digit’s suspected killers, bound them with barbed wire, whipped them

with nettles, injected them with gorilla dung, and cast evil spells she

gleaned from African sorcery. Even after receiving an exigent message

from her primary funder that she desist, she continued, bent on revenge.

She crippled the cattle on which the local communities relied for food,

kidnapped a 4-year-old child, set a house on fire. Such tactics likely

provoked her murder, after which she was buried beside Digit with a

marker that bore her favorite nickname, Nyiramachabelli, which she

understood to mean “the old woman who lives alone in the mountains

without a man.” In death as in life, she couldn’t have made her

allegiances more explicit.

Celebrity fur baby

Then

there is Ruth Harkness, the matriarch of them all. Ruth was the first

woman to have an intimate relationship with a wild animal that also

functioned as public spectacle. Few people had ever seen a live panda

when the glamorous New York City fashion stylist pluckily set out for

the jungles of Szechuan in 1936 to capture one. To the astonishment of

big-game hunters and the press, she found an infant, eyes sealed shut,

crying in a tree. The cub drank greedily from the baby bottle Ruth had

thought to pack, and from then on, the two were inseparable.

Ruth named the animal Su-Lin but called it “Baby.” Refusing cages and

leashes, she held Su-Lin in her arms. They co-slept. She fed on demand,

at all hours of the night. She burped the panda on her shoulder,

massaged its belly, and called a pediatrician to advise on the animal’s

“colic.” The panda soothed herself by sucking Ruth’s earlobes. Ruth

weathered a winter in New York with the windows open, believing the cold

air better for the furry animal. Even after the panda was deposited at

Chicago’s Brookfield Zoo, she persisted in directing Su-Lin’s diet.

The press never tired of Ruth and Su-Lin. With Su-Lin on his lap,

Theodore Roosevelt declared that he would just as soon taxidermy Su-Lin

as stuff his own child—and ushered in an era of the panda as symbol of

animal conservation and Chinese pride. By the end of the 1930s, Ruth was

a household name and a brand icon for Quaker Oats.

In 1938, Ruth imported a second baby panda, Mei-Mei, and then returned

to China for a third. But this one bristled at Ruth’s touch and

constantly tried to escape, which Ruth found deeply unsettling. At the

same time, the zoo mania for pandas led to ill-conceived and inhumane

expeditions in which double or triple the number of commissioned animals

was captured. In a span of less than five years, the panda population

showed signs of decimation.

Confessing to a friend, “I think this sort of thing is over for me,”

Ruth dismayed her backers by announcing she would return her third panda

to the wild. The gesture was entirely at odds with her milieu’s

attitudes toward wild animals. By the time of her death in 1947, “the

panda lady” was impoverished and forgotten.

Ahead, or out of time?

Ruth

Harkness, Dian Fossey, and other women prioritized their animal

companions above their hu wild. Such anecdotes are usually read man

community. They loved their animals as equals, and their relationships

compelled considerable sacrifices. At some future point in time, these

women won’t be remembered for their eccentricity, but for their intrepid

sensitivity. Each of them heard and responded to the internal stirrings

of a creature that was believed to lack inwardness, and each of them

came to understand that loving an animal obliged them to honor the

creature’s autonomy.

Dawn cannot be blamed for the tortuous circumstances of Tilikum’s

capture, for his years of cramped confinement, for his isolation from

his social group, for his bullying from other captive orcas. But perhaps

she can be blamed for trusting a business that didn’t love the whales

as much as she did. “When you look into their eyes, you know someone is

home. Someone is looking back,” says a SeaWorld trainer in Blackfish.

Dawn knew someone was looking back, and she must have been forced

sometimes to pretend she didn’t.

Sasha

Archibald is a writer and curator based in Los Angeles. Her work has

appeared in The Believer, Los Angeles Review of Books, and other

magazines. She is a frequent contributor and the former editor of

Cabinet Magazine.