Birds of a feather

Tyrolean homesteader makes an exotic nest in Corrales

The sound is unmistakable—if you know what it is. Otherwise, you’ll be liable to think the soundtrack to Jungle Book, except that you’re standing in the Corrales bosque on a dirt road amid cow manure, horses and sheep.

“They scream,” admits Peter Kaserer, nodding toward his three peacocks strutting around their large arbor in the shade of giant cottonwoods. With their loud, piercing cries, peacocks are often blamed for destroying the peace as suburban pets. But in Corrales, no worries. Kaserer lives on the south end of the village, where the foliage is dense and the lots are two acres or more. He and his wife, Alana McGrattan, have 27 acres and few neighbors: One used to live in India, where peacocks originate; another spent time in Sri Lanka; and the couple across the street were big-game hunters in Africa, so all three families tend to find the shrieking nostalgic.

Still, Kaserer’s peacocks make an arresting sight for anyone who happens across them unprepared. For one thing, these birds are big, and appear even bigger with their feathered trains. Two are the traditional blue, and one is a stupendous snowy white, a mutation. A Christmas gift from Alana, the bird was dubbed “Cristatus” in a holiday pun on the species name, Pavo cristatus.

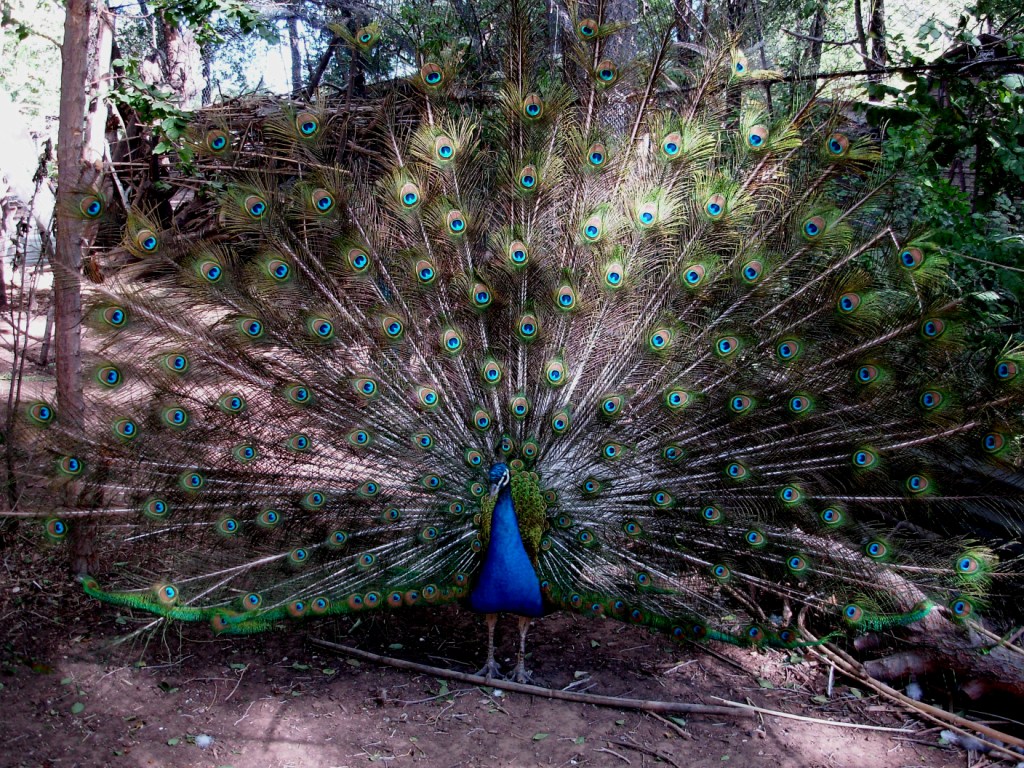

One of the blues suddenly fans its plumes into the shower of iridescent eyes that is designed to bring the plain-looking peahen to her knees. He stamps his feet and turns in a slow dance as we slip into the arbor, a large homemade pen of rebar and netting woven among the trees that has survived 20 Corrales winters. The peahen walks by, unimpressed.

Kaserer actually built this arbor for some golden pheasants, his first bird addiction (peacocks also being a form of pheasant). But the netting failed to keep out hungry raccoons, who would bite off his precious pets’ heads and abscond with the bodies. Kaserer now keeps his golden pheasants in an enclosed cage.

The peacocks, on the other hand, can fly high into the trees to escape predators. They are hardy in cold and snow, despite their tropical origins, and Kaserer says they are easy to care for, making them popular as pets. In fact, two other owners live within screaming distance of his birds, causing a chain-reaction racket when one decides to shriek.

“They take the same feed as chickens, except I give them dog food because they need the protein—for their feathers,” Kaserer says. They also eat alfalfa and fruit. And they make great

watch dogs, he adds. As for affection, well. “Birds are not exactly affectionate,” he admits. “It’s their eyes. The face of a bird does not bring to mind affection. But they do come up to you,

like all animals, if you have food.”

You would swear nevertheless that peacocks offer benedictions, once you are blessed with a display. Cristatus suddenly decides it’s time to show that white is might, and fans a huge lacy plumage that is breathtaking for its rarity. Kaserer sighs, still bewitched by the sight—ethereal, both showy and pure, otherworldly. After he acquired the three cocks, he got them a

hen as extra inducement to flash.

That hen laid four eggs this year, but Kaserer isn’t committed to breeding—not with his fields to mow, horses to feed, a small herd of cows with calves, chickens, pheasants, and all the work that goes with country living. A native of the Tyrol in Austria, Kaserer grew up on a farm and still loves the country. But it’s a lot of work keeping up their property, an inheritance from McGrattan’s aunt that stretches from Loma Larga to Corrales Road.

It’s not just the screaming peacocks, by a long shot. Gophers dig holes in their terraced fields, undermining the walls until they collapse; coyotes pounce on mice and rabbits that flee his mowing blades. Wild ring-necked pheasants, ancestor of the goldens, wander the property bordered by elms, Russian olives, mulberry trees, and cottonwoods.

But he loves it here, Kaserer says, surveying the property from its high end at Loma Larga. His fields of alfalfa, fescue, and wheat grass stair-step down to a postcard view of the Sandia.

“When everything is green,” he says of his native climate, “you have a tendency to go blind.” He gets back in his old farm truck and rattles down the dirt lane that was recently donated by McGrattan as a new equestrian shortcut to Loma Larga. The couple has also put six of their 27 acres into a conservation easement to help preserve open space in the bosque. With the

Sandia on one side and Intel looming over them on the other, they know what they have in this oasis.

Not so their peacocks, who take their jungle environment for granted. Pavo, the older blue at 15 or more years, looked a bit ragged with the onset of summer; peacocks shed their spectacular train by July. Kaserer found him running loose in the bosque, and easily captured him. The younger blue, Junior, is about 7.

Peacocks live about 20 years and sometimes as long as 40. Even without the presence of their hen, Kaserer’s cocks fan their tail feathers for any visitor they fancy, a showy abundance of natural beauty for no reason at all, for the pure glory of nature—the very image of the Corrales bosque itself.