SUSAN SEHI-SMITH is a passionate advocate for the charity she founded last year, Paws to People: Bridges to Cures. Its mission, known as comparative studies, has been a growing interest for years, edging out her many other enthusiasms to become a full-time cause.

The biggest challenge of the mission so far, however, has been explaining to people exactly what it is. For every visitor to her table at a pet event who listens intently, a fair number of eyes wander to the cute furry distractions nearby.

Sehi-Smith has no shortage of cute and furry at her disposal. She and husband Stephen live with an excitable family of American Eskimo dogs affectionately known as the White Dog Army, which has its own blog featuring an entertaining cast of characters: Siku (The White Dog), Nuka (Another White Dog), Quinn (The Other White Dog), Puff (Still Another White Dog), YoYoMa (Yet Another White Dog), and Oso (Oh, Another White Dog). Three have since passed on, and a recent addition to the white dog family named Zsofi a is not, in fact, white.

At whitedogblog blogspot.com, Sue practices her breezy, fluent, clearly pleasurable talent for writing, honed as creative director for an educational materials company. She has been a painter of expressionistic acrylics for years. Stephen, an architect studying for his MBA, loves classic and exotic cars, particularly Mercedes. The couple are enthusiastic promoters of alternative energy, and have at various times cheerfully shared their quarters with a three-legged iguana, two Bearded Dragons, a Spur-Heeled Tortoise, two Sugar Gliders, and a pet tarantula—all before the White Dog Army came along.

None of which is the subject of this article.

Sue explains that their first dog, a Sheltie named Sheena, came to them abused and had to learn to trust humans again. Sheena taught them to be doting doggie parents. When she became oddly lethargic, exploratory surgery revealed that the 14-year-old dog was riddled with cancer, and most likely in pain. Sue opted to spare her further agony, and let her go without even a chance to say goodbye. That was heart-wrenching.

Two months later, when Stephen brought home the American Eskimo dog Siku, “she melted all the ice I had built up in my heart,” Sue said. The rest of the army followed, starting with Quinn, who was snatched from death row. More rescue dogs followed, and currently four of their six dogs have special needs.

In

2009, Susan and Stephen went up to Fort Collins, Colo., to participate

in a fundraising walk held by a canine cancer organization, founded by a

man who had lost his dog to cancer. It was there that the couple

learned about innovative work being done to fight cancer in dogs and

humans alike through research that crosses species lines.

“It was a very emotional outpouring,” Sue says of the event, where

cancer survivors walked with those grieving dogs lost to the disease.

Sue had a favorite aunt she had cared for at home in Chicago through

years of difficult cancer treatments, and since she had lost Sheena to

the same disease, the cause touched her personally. She joined the board

of the national organization and put together fundraising events in Rio

Rancho and Bernalillo in 2011 and 2012.

In

2013, after learning more about the field of comparative studies, she

founded Paws to People, which she vowed would devote a greater share of

donations to the cause than the other group did.

The cause turned out to be much greater than fighting cancer or any

other disease, though humans and animals do share nearly 400 serious

diseases in common. Cancer provides an especially good example of the

potential of comparative research, Sehi-Smith says, because modern

medicine has made no significant advances in treatment despite millions

of dollars poured into research.

“The best we can do is the same three things—chemotherapy, radiation,

surgery— none of which are cures,” she says. In dogs, treatment aims

only to extend life, since it is so difficult to gauge the distress

caused by the usual human treatments. “The unspoken goal is not to cure,

but to maintain the current state.

“To me that’s a futile approach,” she adds. “Why not think outside the box?”

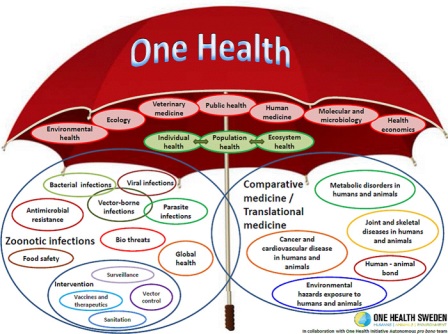

The ambitious reach of comparative studies is expressed well by the

group known as One Health Initiative, which promotes “a worldwide

strategy for expanding interdisciplinary collaborations and

communications in all aspects of health care for humans, animals, and

the environment.”

The group aims to foster collaboration, not only between medical and

veterinary research, but across the fields of environmental health,

ecology, food safety, biological threats, zoonotic infections, and the

economics of health care. “Health” is conceived as a single umbrella

that encompasses the well-being of the Earth and all its inhabitants,

“recognizing that human health ..., animal health, and ecosystem health

are inextricably linked...”

The bestselling nonfiction title Zoobiquity popularized this idea in

the United States early last year. Cardiologist Barbara

Natterson-Horowitz saw similarities in heart disease she treated in a

monkey and in her own human practice, but found that doctors and

veterinarians rarely share information. She set out to explore

crossspecies similarities in disease and treatment, and found a world of

unexplored opportunity.

“Cancer is cancer, regardless of the host,” Sehi-Smith explains. “All

species are connected to start with.” This basic understanding has been

lost with the fragmentation of scientific disciplines since the days

when veterinarian and doctor were more interchangeable.

One thing comparative studies is not, Sehi-Smith emphasizes, is

laboratory testing on animals. “It’s compassionate medicine, because it

has to treat animal subjects the same as human” to make valid

comparisons. Dogs are ideal subjects in this regard, she says, because

they live our lives and share our diseases, from cancer and heart

disease to diabetes, depression, and dementia.

Paws to People, or P2P for short, is pursuing donations to provide

seed funding for innovative research of the kind that will not win the

support of “big pharma.” Sehi-Smith reports that a donor has pledged to

match donations up to $3,000, and that they hope to award up to three

research grants initially.

The group’s advisory board includes veterinary oncologist Barbara

Kitchell and geriatric specialist Phil Ries of VCA animal hospitals, and

Deborah Openden of the Breast Cancer Resource Center, among others. The

board had its first meeting in June, and Sehi-Smith came away “charged

and inspired!” The group has a number of fundraisers planned for fall,

including a shoe fundraising drive (see box).

The challenge remains “getting the public to see the immediacy of what

we do, versus take this puppy home today and save its life,” she says—a

mission that the White Dog Army, for all its charms, can’t quite

deliver on a human scale. “It’s putting faith in the idea that this new

paradigm can come.”

Visit Paws to People on Facebook, at bridgestocures.org, by email or at 505-232-7996 to donate shoes in any condition to help reach their goal of 7,500 donated pairs.