A place that’s safe for chicks

Meet farmer Erin Parker- Rich, proprietress of Hip Chik Farms in Corrales—a name that really seems to fit.

You will not see this farmer curse, spit, or allow her neck to burn a telltale political hue. Languidly she floats between her cultivated quarter-acre right off Corrales Road, lively with greens and wildflowers in late summer, and a grassy half-acre where 180 hens roam free, never bothered by coyotes. (Yes, never.) There is in her not a trace of the cynical bitterness of most who farm Western soils.

Erin Parker-Rich has been a farmer for all of four years, and she has started over on a new piece of land four times. A regular presence at the Corrales Growers Market with her immaculate, lush heritage greens, she now runs the vegetable farm, chicken ranch, and market operations with daughter Lily, age 8, plus one employee.

“I think I’m just stubborn,” she concludes in attempting to explain how all this came about after getting a Criminology degree from UNM. A member of the community-supported agriculture co-op Los Poblanos (now Skarsgard Farms), she continually asked gardening advice of farmer Monte Skarsgard, which he continually answered.

“We borrowed some land in Corrales, and learned mostly by messing things up,” she says of her early efforts with husband Patrick Rich, when they lived together in Los Ranchos. “I really had no idea.”

Like many gardeners, they ended up growing more than they could use. When it became a whole lot more, they started to sell. Their next farm was behind Farm & Table restaurant in the North Valley, where they also supplied diners at the new foodie destination. Then they added chickens, which Erin reasoned made sense to supplement a farm income. From 12 hens, the operation boomed to around 180, half of which had to live on the land borrowed in Corrales.

“Not being poultry handlers, it was a steep learning curve,” she admits. “We learned through trial and error, mostly.” Her current flock of heritage Ameraucana, Ancona, and prolific Red Star chickens is thus the second, since the hens are sold off as they stop producing.

Going from backyard coop to egg production took some education, but Parker-Rich would corner Tom Delehanty of Pollo Real whenever she saw him, as well as Skarsgard. “I’m a handson learner,” she smiles.

A major obstacle back then was getting to the Corrales field every day to herd the hens in for the night. “Knowing about the coyote problem in Corrales, I just threw out one day that it would be great if there were such a thing as an automatic chicken door,” she says, indicating the large yellow hen house built on a cotton trailer. “Looking on the Internet, it turns out there is such a thing.”

She explained the device to her father, a retired engineer, who created a solar-powered automatic door that shuts the hens in at dusk. Birds have a homing instinct, and quickly learned to fly in for the night before the doors closed. “If you want to be scared, come at night and fling open the doors,” she says. All 180 hens are stacked inside like books in a library.

Another unforeseen obstacle was moving all those chickens when she relocated this year to Corrales. Despite being on wheels, the hen house isn’t designed to roll. “We packed them—lovingly—in a U-Haul trailer, three trips.”

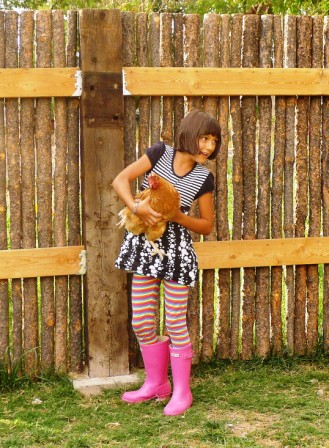

Which brings us to Lily’s official job on the farm, as Chicken Wrangler. It’s her task to catch errant birds that might make a mess in the vegetable garden, since “I don’t exactly shut the gate all the time,” she admits.

There’s a trick to catching chickens, apparently. “You have to get them cornered. They can fly over you,” Lily explains. “If you put your hand on them, they squat down. They think you’re a rooster.” She demonstrates with old Bertha, gathering the hen up with an easy swoop. Bertha is among the few hens that has earned a name by being people-friendly, and does not seem to mind being cuddled. The other chickens scoot away nervously when people approach, unless those people are flinging handfuls of feed.

Parker-Rich cannot really explain why she has not lost any birds to predation. “I don’t open the door until 9, and by then there’s traffic on the road,” she says of the natural barrier formed by busy Corrales Road. “I see coyotes in the ditch, and even in my driveway, but they seem more nervous, like they want to get somewhere.” She thinks it’s just common sense not to have chickens wandering around at the wrong hour, though other vendors at the Growers Market shake their heads at her and wag fingers.

The hens lay 70 to 100 eggs a day, which translates to 40 or 45 dozen eggs to take to market on Saturdays. In winter the eggs go to La Montanita Co-op, or Farm & Table. None go to waste. Fridays through Sundays are busy for the farm, as everything has to be readied for market. Otherwise, the hens are fed twice daily, the house mucked out every month or two.

The only other residents at Hip Chik Farms are a Maine Coon cat (also female), and a hive of honeybees for pollination. “I thought about doing goats, and I would really like a cow,” the farmer says wistfully. “But I would need help milking it. And really, how much can I do?”

The secret to hip farming in Corrales seems to be doing everything you can—and no more. “I enjoy farming, and being outside all day kind of allows me to see the tiny details and intricacies of life, and how we are all connected,” says Parker-Rich. “Plus … the weeds don’t talk back.”