Large animals in the Sandia

are finding fewer ways to leave their lovely biosphere zoo

Behind the funny story of a bear caught napping in a Northeast Heights yard, or the poor mountain lion killed while crossing Montano Road is a widely overlooked, much sadder truth: Animals need to cross wide distances to survive.

It isn’t just individual creatures or families in search of food or water, but whole species across regions like New Mexico or the Rocky Mountains that depend on migration to stay healthy.

The reasons are obvious when you consider their evolution: Like humans, large mammals such as bears, wolves, elk, cougar, and bison have always ranged widely—seasonally or as necessary—to survive environmental changes like fire or drought, and to mix up the genetic pool and prevent inbreeding.

We are fortunate in New Mexico to have so much land available for wildlife to roam, starting with the visible daily reminder of the majestic Sandia mountains—62,000 acres, of which 60 percent is protected as wilderness, meaning no guns or motor vehicles allowed. Animals

should be free to carry on here pretty much as they have for millennia. But increasingly—and especially on the Sandia—animals are trapped in their lovely biosphere zoo while buildings, concrete, and pavement hem them in on all sides.

That’s what caught the attention of Elise Van Arsdale and Mitch Johnson, nature-lovers from Placitas who were out hiking on the Sandia about six years ago when they got a good vantage point on the mountain’s north side. Van Arsdale always enjoyed watching wild horses come to drink at Las Huertas Creek below her property, and knew that a lot of wildlife relied on the water source. Now it became clear why: Houses and roads had sprung up on all sides of the mountain except this narrow corridor to the north. Elk, antelope, deer, wild horses, and other mammals were all being funneled into Perdiz Canyon at the foot of the Crest of Montezuma, which is visible from Corrales as the last ridge tucked behind the mountain to the left.

Elsewhere, houses and highways blocked access to the open mesa, to the Jemez and the Sangre de Cristo ranges. The little canyon below Van Arsdale’s house had become a wildlife highway. With fellow environmentalist Peter Callen, she and Johnson started a nonprofit group in 2007 called Pathways: Wildlife Corridors of New Mexico (pathwayswc.wordpress.com), with the simple goal of ensuring that this ribbon of land would stay wild, so the animals would not be trapped.

Continental Concern

Little did they know what they were getting into, Callen says now. Their first goal was to get the Crest of Montezuma included in the Forest Service boundary, with the rest of the mountain. But a bill to transfer that land from the Bureau of Land Management (introduced by Rep. Martin Heinrich last January) has been stalled in House subcommittee since February.

Meanwhile, Pathways learned they were part of a much larger concern growing throughout New Mexico and the West. Across the mountain in Tijeras, a coalition of animal-lovers had been working since 2003 to create safe passage for wildlife across I-40, identified in surveys as the most critical highway passage for wildlife in the state—another narrow corridor that had become a high-speed kill zone for animals crossing between the northern and southern sections of the Cibola National Forest.

The Tijeras Canyon Safe Passage Coalition didn’t get much press at the time, but theirs was the state’s best success story yet in keeping wildlife moving freely. Working with the New Mexico Department of Transportation and state Game & Fish Department, local activists succeeded in getting three passageways cleared under I-40, with fencing to funnel deer and other animals under, instead of up onto, the Interstate.

Their timing was lucky, says Kurt Menke, co-chair of the coalition. Highway construction had been planned anyway, and Governor Richardson signed a bill in 2003 directing the two agencies to work together to prevent animal-vehicle collisions. From 25 large animal collisions a year on I-40 through Tijeras Canyon, the figure dropped to about two a year since the improvements were made.

Elsewhere in the state, however, progress has stalled, says Menke. In 2008 the Western Governors’ Association adopted a Wildlife Corridors Initiative, which prompted two neighboring states to identify critical wildlife passages statewide that they can use in future planning. “Colorado and Arizona have tons more money for wildlife management,” says Callen, of Pathways. “New Mexico has one person appointed at Game & Fish. He’s the only one who’s been able to provide the needed data.”

That person is habitat specialist Mark Watson, called a “hero” by Menke for his work on the Tijeras Canyon passages and safe railroad crossings for bighorn sheep over Abo Canyon in the Manzanos. But Watson concedes that Game & Fish is mostly focused on preventing animal-vehicle collisions, and hasno program addressing wildlife connectivity.

The U.S. Forest Service has even fewer resources to commit to the cause. Zack Parsons, wildlife biologist for the Sandia Ranger District, says he is interested in gathering data on wildlife movements, but the money is not there. “It’s definitely something we’re concerned about, and we’re aware of the importance of it,” he says. “But as far as having a program specific to monitoring movements, we don’t have the resources.”

“In 2003, New Mexico was pretty progressive compared to other Western states,” Menke says of wildlife management. “Now, especially with climate change and renewable energy development, there needs to be investment by the state so we can make good decisions. We have a lot of groups working on it. We need more support from state agencies.”

Meanwhile, a growing number of nonprofit groups, including the Wildlands Network, Rewilding Institute, Defenders of Wildlife, and New Mexico Wilderness Alliance, are working feverishly to establish four transcontinental wildlife corridors to guard against mass extinctions: from Baja to Alaska along the Pacific Coast; east-west across Canada and the Great Lakes region; from the Everglades to the Arctic; and the so-called Spine of the Continent initiative along the Rockies from Mexico to Alaska.

It is this last, so-called Western Wildway that has a giant gap right here in Albuquerque/Santa Fe. “That 100-mile missing link is critical to ultimately creating this huge continental wildway,” said Kim Vacariu, western director for the Wildlands Network, which is coordinating the continent-wide efforts. A coalition of local groups called New Mexico Wildways (nmwildways.com) was formed in 2009 specifically to address this “missing link.”

Commonly known as the Galisteo Basin, the broad plain connecting the Sandia and Sangre de Cristo ranges is made up mostly of private land. That makes protection especially difficult, says Jan-Willem Jansens, executive director of Earth Works Institute in Santa Fe. The first threat, oil and gas development in the basin in 2007-2008, was stopped partly because the area’s identification as a wildlife linkage helped persuade Gov. Richardson’s administration to pass a moratorium on drilling.

Says Van Arsdale, of Pathways: “We gradually began to realize that the private lands we were concerned about, as well as the Crest of Montezuma, were vitally important to the health and well-being of wildlife exactly because of where they were situated on the spine of the continent.”

Islands of Extinction

For more than a century, nature-lovers concerned about extinction have worked to protect parcels of wild land from development so plants and animals could continue reproducing undisturbed. But that strategy has led to a patchwork of wilderness “islands” where species can be wiped out by a single catastrophe, a shift in the ecological balance, or gradual weakening from inbreeding.

The loss of bighorn sheep on the Sandia during the 1980s may have been an early signal that our mountain is turning into just such an island. “As big as it looks to us, the Sandia is isolated geographically and biologically by the city of Albuquerque,” says Callen. “In the past, animals could come to the river, cross the plains to the Jemez and Sangre de Cristo.”

Callen has recorded tracks of deer, mountain lion, and bear at Las Huertas Creek—but no such signs have been documented downstream. “Once people become aware, they can start to make choices,” he says of wildlife movement. But for the Sandia, “it’s possible that this population is already somewhat stuck.”

A Mosaic Message Composed by Many

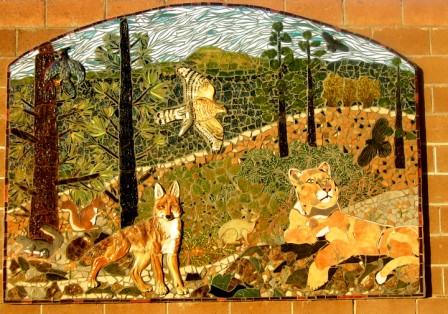

One of the six mosaic murals at the Placitas Recycling Center pictures a high-country habitat, incorporating ceramic bas-relief animals made by different artists.

Wildlife corridors are not a widely understood concept, so a group of artists affiliated with the group Pathways: Wildlife Corridors of New Mexico launched an ambitious project in spring 2008 for large mosaic murals visible from Highway 165. The multi-year community project brought together 240 people, including professional artists, volunteers from around Albuquerque, and 147 children from three schools in a collaborative process that racked up hundreds of volunteer hours. Each of the six murals on the walls of the Placitas Recycling Center measures about 6 by 9 feet, and represents a local wildlife habitat. A title panel reads “Protect our Wildlife Corridors”; another lists all the volunteers. Work has begun on the final panel, and everyone is welcome to contribute and learn mosaic technique; no experience is necessary. Contact Laura Robbins at 867-3189 or laura@laurarobbinsmosaics.com.