THE BRONZE IMAGE of Santa Fe’s patron saint gazes out from the Cathedral

Basilica, hand extended past the boutiques and art galleries toward the

central plaza of the City Wealthy. Ignored here by tourists strolling by

with their shopping bags and caffè lattes are the ones whom St. Francis

of Assisi held dear—the poor, the homeless, the wandering.

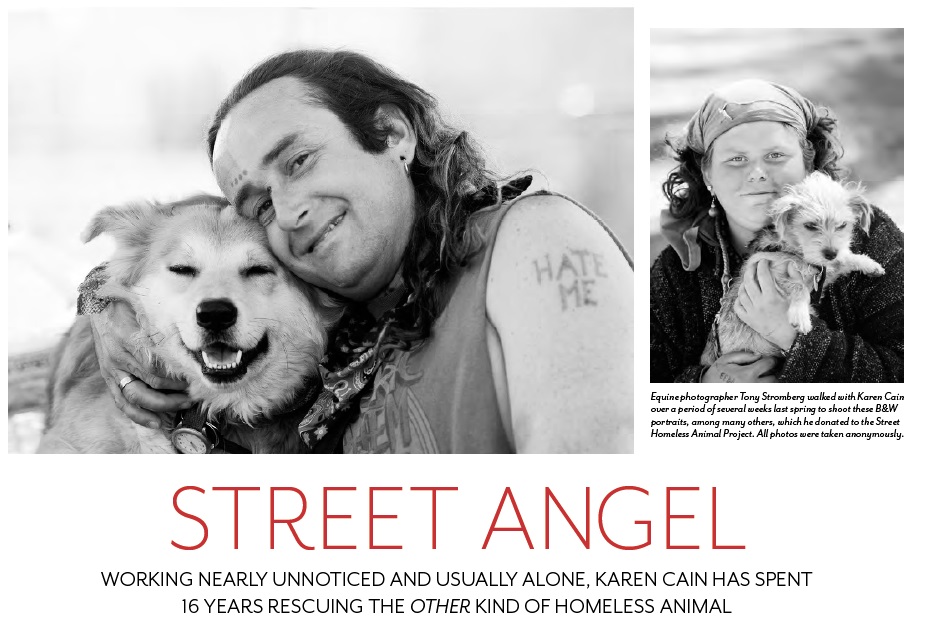

If one could imagine a modern-day St. Francis among Santa Fe’s

restaurants and designer showrooms, he might not be quite what you’d

expect. He might turn out to be a petite blonde from Dallas who walks

the streets in all kinds of weather, stopping to converse with scruffy

kids on skateboards and old men panhandling on the corner. Her sweet demeanor and resumé as a counselor and director of a Santa Fe nonprofit will not tell you who she is or what she does. For Karen Cain appears to have what they call a street ministry—though she would never call it that herself. Under the heading of Street Homeless Animal Project, Cain literally walks the walk and talks the talk, extending charity and compassion to anyone who looks down and out, especially if they are with an animal.

“Any one of us could be in this situation, and we have a moral and ethical obligation to help each other,” she says. We are put here on Earth for a reason, she says. How can you walk by and ignore someone in distress?

Cain cannot. She has always been an animal-lover, was active with PETA and Animal Connection Texas when she lived in Dallas. When she moved to Santa Fe in 1998 and got her license as a counselor, concern for the two-legged met that for four.

She recalls a day when she saw a homeless man and his dog, and “one or both of them were limping.” She stopped to see if they needed help. “From there, literally out of the trunk of my car I would provide leashes, food, whatever was needed.” Soon she couldn’t stop noticing people and their animals living on the street, struggling to remain together and stay alive.

If

you live on the street—or in your car, in the case of many women—you

are constantly asked to choose between your own well-being and that of

your dog, Cain explains. Shelters do not allow animals, nor do public

buses or most institutions, and it’s not always easy to find someone you

trust to look after your companion while you get a shower or a meal.

“These animals are their family, just like for you and me”—only

completely dependent on each other for comfort, companionship, safety,

and warmth. If you are homeless, your animal may be your only real

friend, your only remaining family. That’s why so many homeless people

would rather sleep under a bridge than in a shelter, she explains.

Cain worked alone and with her mother, paying for everything out of

pocket, for many years. As a counselor to young people at the St.

Elizabeth Shelter, she often came across people who needed help with

their animals.

“The need was so great, we were so busy,” she says. Eventually her

mother helped set her up to do the work full-time. In 2009 she

established a tax-exempt nonprofit to accept donations—11 years after

the fact.

To this day, SHAP remains practically invisible among Santa Fe’s

600-plus nonprofit agencies, its mission too gritty to compete with the

more cuddly cause of rescuing animals left homeless by humans, not with

them.

Cain admits to ignoring what she calls “the rest of it”—fundraising,

marketing, administration. “I feel the most comfortable out here,” she

says, “sitting on the curb at Allsup’s. Because it is what it is.”

Most of the people she helps these days are under 21, a nomadic

population who call themselves “travelers” and head to warmer climates

in winter by hitchhiking or jumping trains. This has helped spread word

of SHAP’s work from coast to coast.

Cain recalls a visit to San Francisco some years ago, when she stopped

to talk with some kids in the Haight-Ashbury District, only to discover

that they remembered her as the woman in Santa Fe who helped with their

dog. Indeed, to the shadow residents of Santa Fe, she is the one who

feeds your starving children, who gets a doctor for your dying mother.

“No other organization is doing what SHAP is doing,” says Tom

Alexander, a longtime animal activist who joined the board after hearing

about the group in 2011. Cain received a Milagro Award from Animal

Protection of New Mexico (APNM), where Alexander is on the board.

Earlier this year, he became president of the SHAP board.

“I think the work is much needed,” he says, after having worked with

nearly every animal charity in Santa Fe, none of which serve this

population. “These folks have absolutely no resources.” Yet the

homeless, says Alexander, often are doing all they can not to abandon

their companions.

Estimates of the homeless population in Santa Fe range from 500 on any

given night to double that number, according to the New Mexico

Coalition to End Homelessness. Alexander believes SHAP serves a core

population of around 300 people who live in Santa Fe year round.

“I’ve heard people say homeless people shouldn’t have animals. But the

fact is that they do and always have, and for many of them it’s the

only family they have,” he says. “I always come back to, never mind the

human, it’s the animal that’s in trouble, and we want to help in

whatever way we can.”

Cain limits her resources to people living on the street 24/7 with a

companion animal, or who have found transitional housing only in the

past six months. Clients must also agree to spay/ neuter, which she

admits has met with “a fair amount of resistance” over the years.

“There’s just too much suffering,”

Cain says of the overpopulation of stray animals. SHAP pays for the

surgery and any necessary boarding, and “it has been difficult, but it

is the big stipulation.” Most people, because she shows up and has

earned their trust, eventually come around.

Amid the throngs of tourists who flock to Santa Fe year round, the

homeless keep a low profile and try to avoid being set upon by police.

Cain finds them in the Plaza and in Cathedral Park, near the main

library, in Railyard Park, and at the mini park at Gaspar and Water

streets known as The Rock.

She greets everyone so warmly, it’s hard to tell who is a stranger. “I

make it my business,” she says, hastening her step to see who is being

pulled aside by a cop. Only recently did the new mayor of Santa Fe,

Javier Gonzalez, become aware of their public service, she says.

If people need dog food, SHAP will arrange to have a bag ready for

pickup at Petco. If their dog needs shots or veterinary care, SHAP has

an arrangement with Smith Veterinary Clinic to provide for them, and now

has veterinarian Leslie Eisert of Eldorado Animal Clinic doing outreach

on the street.

Medical care is the program’s biggest expense, especially after a rash

of parvo virus this year led to bills of $500 to $2,500 per animal.

“I’ll do everything— beg, borrow, but not steal,” Cain says. “Because

this is their family.”

Another challenge is finding temporary foster homes. Most clients’

dogs are large—pit bulls and pit mixes, the kinds of dogs often

abandoned or discarded by the side of the road, like the humans who

rescue them.

“We’re a huge dumping society,” Cain says with soft ferocity. “You become too much trouble, for whatever reason.

“Sometimes I wish I didn’t care,” she adds. “But I have to look myself

in the mirror every morning. And at the end of the day, what have you

accomplished? So I have to help.”

"I'd rather die"

“WE'D HAVE AN apartment for you if you’d just give up your dog,” they

tell me. I’d rather die than give up my dog. My little terrier, Mattie,

is now five years old. I found her on a state highway in southern

Missouri when she was only six weeks old. I remember picking her up out

of the weeds and looking right in her eyes and saying, “God gave you to

me.” Those words were prophetic—not words I would normally say, but

indeed foreshadowing.

How would I know then that she would be the most reliable, protective

and loving companion I have ever known? When I was grieving and crazy

depressed, I would hold her tight and cry until I fell asleep. She would

then wiggle out of my arms and lie down at the foot of my sleeping bag,

listening for any weird noises in the night. I also moved from home

with two dear, sweet cats, and both of them have died. That’s about all I

can say about that without bawling.

Some folks say I should apply for disability because I am suicidal and

depressed, but I don’t want long-term help. I just need a toehold out

of this deep crevasse I am in, this dark night of the soul. — From “Homeless in Santa Fe,” by a woman named Cynthia (Santa Fe Reporter, Jan. 25, 2012)