IMAGINE

THAT THE CITY you live in votes to ban your dog and all that look like

her. Animal control knocks at the door and seizes your Princess, and you

have 30 days to go to court with a nonresident who will swear to adopt

her, or she will be put to death. Not possible in America, you say. Yet

this is precisely what has happened— unbeknownst to most people—in the

city of Denver over the last decade.

Desiree Arnold was one of those people. Her dog Coco was seized by

animal control in June 2008, and because it was the second time for the

dog — whom she did originally move out of the county, only to become

concerned about her care and bring her home — there would be no second

chances. Coco would be euthanized. Arnold sued the city, but as the case

dragged on, her dog began to fall apart. Every time she went to visit

the city shelter, Coco would whine and cry, wanting desperately to go

home. Heartbroken, Arnold could not keep watching her dog suffer. She

gave up the fight, and was handed her dog’s body in a garbage bag.

If you love your dog, you cannot watch her tell this story without

feeling crushed. The dog was sweet and gentle, as she explains in the

documentary Beyond the Myth—a loved member of the family. The city of

Denver has the nation’s most notorious ban on pit bulls, which has led

to the seizure of 1,900 dogs since 1989, of which 1,453 were put to

death. But the cruelest moment in its history came in 2005, when the

city successfully fought a statewide prohibition on laws banning certain

dog breeds. A notice appeared in the newspaper that Denver’s ban was

back in effect, and 30 days later, officers knocked on doors and carried

off pets to kill.

From where we sit in New Mexico, it seems upside down. This is Colorado we’re talking about, the state with such a shortage of adoptable animals, until recently it took in thousands of homeless animals from New Mexico every year.

Yet the fact is that such a cruel, senseless, draconian law could not have been enacted in Albuquerque—though legislators here have surely tried (most recently, State Sen. Sue Wilson Beffort of Bernalillo in 2012). Pit bulls are the third most popular breed of dog in New Mexico after Chihuahuas and Labrador Retrievers, according to this year’s annual survey by Banfield pet hospitals—and they live with families across the economic spectrum. “Some of our largest donors own multiple pit bulls, and these are not low-income folks,” says Peggy Weigle, director of Animal Humane New Mexico. “People love their pit bulls.” If our animal shelters are full of homeless pits, it is partly because they are so very popular; the Albuquerque city shelters also counted some 107 Chihuahuas in its latest inventory.

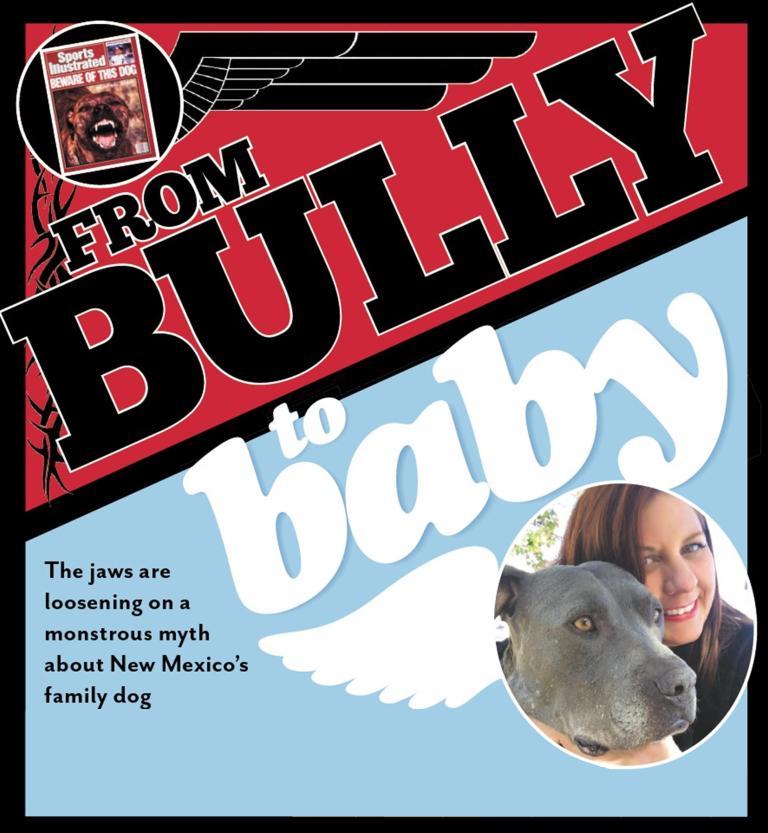

There is no denying, however, that “pitties” take longer to get adopted and are euthanized at nearly three times the rate of Chihuahuas—and not only because large dogs are harder to place. Even in New Mexico, pit bulls have an image problem, no matter how many people love them and swear that they make great family pets. Experts may testify that breed bans are unscientific, illogical, and ineffective—as they have done for a decade—but they are drowned out by the impact of sensational mauling stories and politicians capitalizing on public fear. It has proved simple enough to get large numbers of people to believe that Muslims “hate freedom,” young black men are violent, and blondes are dumb. Why should it be any different for the all-American dog?

“THE AMERICAN DOG” is what the pit bull is labeled in a beautifully written story in the August 2014 Esquire magazine by Tom Junod, who pens a long meditation on the strange public relations gap between his cute, silly family dog and the crimes committed elsewhere by dogs that bear a superficial resemblance to him.

“Pit bull,” he reminds us, is not even a breed of dog. The vast majority of dogs described this way are mixed breeds—in Albuquerque the mix is often Labrador Retriever—or belong to one of two dozen breeds that have been called pit bulls in various times and places. What marks these dogs is a certain look, now affectionately known as “blockhead.”

Square-jawed, muscular, and squat, so-called pit bulls cannot be identified by DNA testing. There are, in other words, no pit bull genes, meaning the 47-point checklist that Miami animal control uses to determine if a dog is at least half pit bull would be laughable if it were not actually used to condemn people’s dogs. As Junod put it, any dog crossed with a pit bull is a pit bull, and if that dog bites, it’s always the pit bull part that bit.

Jeff

Nichols, an Albuquerque veterinarian and well-known animal behavior

expert, says there is no heritable trait such as “viciousness.” “The

genetic issue is very complex,” he told an audience during Pitbull

Awareness Week events in November. It is impossible to predict traits

even in the most rigidly controlled breed lines— which is why so many

dogs bred to fight end up rejected and killed. “It’s remarkably complex,

and to reduce it to breed is a ridiculous oversimplification.”

Yet as recently as June 2014, no less a self-appointed authority than

Time magazine ran an article called “The Problem with Pitbulls,” which

resuscitated the tired rumors debunked years hence. Time later had to

publish a correction stating that the horrifying attack at the center of

author Charlotte Alter’s complaint— the mauling of a 3-year-old by a

pit bull—apparently never took place.

IF THERE IS a

viciousness that adheres to pit bulls, it is the circularity of the

argument about their breeding. Three recognized breeds—American

Staffordshire Terrier, American Pit Bull Terrier, and Staffordshire Bull

Terrier— were indeed raised to fight through selection of such traits

as prey drive, pain tolerance, “gameness,” and bite inhibition toward

humans.

This reputation made the dogs popular in the criminal underworld,

where they were sloppily bred in pursuit of the muscular, “bad-ass” look

that made them even more popular with the wrong kind of people. These

poor dogs were often abused and neglected, chained up and encouraged to

be aggressive. Coinciding with the rise of the Mexican drug cartels and

crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s and ’90s, the dogs made an

irresistible poster child for America’s social ills.

The popular media, always drawn to simple ideas and slogans, clamped

its jaws on the pit bull attack genre, perpetuating such strange rumors

as the “locking jaw” theory, or the idea that pit bulls could bite with

greater force than alligators. Politicians came clamoring behind with

demands to ban these dangerous dogs, although dogs have bitten and

mauled humans since the beginning of time.

By the year 2000, breed-specific legislation was being proposed or in

place in 38 states, according to a 2001 report by the Michigan State

University Animal Legal & Historical Center. Banned breeds included

Rottweilers, Chow Chows, German Shepherds, Doberman Pinschers, Mastiffs, and American Bull-dogs, among others.

“In the 1980s and ’90s, it was a very popular thing to do,” says Lou

Guyton, senior director of community initiatives at the ASPCA, noting

that many municipalities have since backed off as the bans failed to

prevent dog attacks. And no wonder—according to Nichols, bite reports

cite many different breeds, most often Labradors, Jack Russell Terriers,

and Cocker Spaniels, all hugely popular dogs.

Unfortunately, pit bulls still find themselves caught in a

self-fulfilling cycle of poverty, abuse, and unsociable behavior that

continues to be supported by discrimination from homeowner associations

and insurance companies. It is not, in fact, any retreat from

scapegoating that accounts for the dogs’ rehabilitation. Rather, it is

the rise of a different voice in the dangerous dog debate, one that is

female, educated, media-savvy, persistent— and a direct challenge to the

image of the dogs as a hyper-macho accessory to drug lords and

gangsters.

MARE ISRAEL WAS

probably the first dog-lover in New Mexico to notice and act on a whole

category of dogs being put to death as a matter of course. In 1999 her

son brought home a dog that was “so ugly it was cute,” she recalls, “and

I asked what it was. When he told me, I said, ‘Are you crazy?!’”

But Israel had done a master’s thesis on manipulation by the media, so

she set out to learn everything she could about these dogs whose image

did not match her reality. After she got a second one— a big black male

named Jake—she consulted with a behaviorist about problems the dog was

having with her wolf hybrid. “They told me I had to put the dog down

because he was a pit bull. I had nine dogs, and they said he would hurt

every dog I had and hurt my mother,” Israel says incredulously.

“It made me so mad,” she said, because Jake was a dog who had been

poked in the eye by babies and done nothing but wiggle happily. The

shelters told her that they had no choice but to kill pit bulls because

good adopters could not be found for them.

“I said, really? Well watch this.” Israel went on to found

Pet-a-Bulls, which has pulled unadoptable dogs from shelters for 15

years and placed them in “wonderful homes,” Israel says: “people at

Sandia, Intel, doctors, lawyers.” She feels the group helped change the

perception that pit bulls belonged with “the kind of people who didn’t

have the resources to care for them,” as she puts it.

Rena Distasio cites a similar wakeup call that led to the founding of

Responsibly Adopting Albuquerque Pitbulls (RAAP). As a volunteer dog

walker for the Albuquerque shelters, she learned about an entire

building full of “big black scary dogs” that were never walked and bound

to be euthanized—pit bulls.

“I had been around the breed my whole life, and decided those dogs

needed enrichment too,” says Distasio. She and Jennifer Conklin founded

their education and advocacy group in 2006 to help get some of those

dogs adopted.

It was a time when the animal rescue movement was coalescing

nationwide, thanks to the Internet and social media. New Mexicans Kassie

Brown, Rachel Starr, and Tiffany Truitt took a page from the success of

the Chicago-based group Pinups for Pitbulls, which published a popular

calendar of fetching models posing with their “bully breeds.” The three

pit bull owners founded The Babes and Bullies in Albuquerque in 2007.

Like the Chicago group, BNB goes out into the community doing

outreach, rather than sitting at tables handing out pamphlets, says

president Tarrah Hobbs. “When people see that we aren’t what they

pictured a pit bull owner to be, I think they’re more open to hearing

our experience with the breed.”

Dog trainer Maria Colbert, former vice-president of Babes and Bullies,

likens the soft approach—more carrot than stick—to what she learned in

sales about approaching people non-judgmentally and seeking common

ground.

The “pin-up” side of the message, she says, is really about marketing.

Women attract attention and help shift the image of pit bulls from

vicious killer to “big bad bully.” This also attracts a younger

generation of women to dog rescue, Colbert says.

PIT BULLS NOW routinely

appear at the sides of articulate women who stand ready to act as

“ambassadors” for the breed and defend against trespasses in the

politics of canine correctness. While the dog fighter tries to stay out

of sight, the Bully Babe is everywhere at public events, on social

media, handing out pamphlets, giving speeches, making documentaries,

writing press releases and letters to the editor.

Her message of the pit bull as ideal family pet and war hero may not

be as compelling as the “time bomb on legs” of 20 years ago. But in New

Mexico, at least, it has taken hold, thanks to constant attention to

rescuing the dogs’ image, as well as their lives.

“In the placement of our dogs, we’re very picky,” explains Angela

Stell, president of NMDog, which places a lot of pit bull type dogs

because of the type of community outreach work they do. “When we choose a

guardian for any one of our dogs, we expect them to be great advocates

for dogs. When we choose a guardian for one of our pitties, we also

expect them to be a great advocate for the breed.”

NMDog often requires adopters to attend basic obedience training,

avoid dog parks, and act responsibly to avoid contributing to a negative

stereotype. “It’s not everybody who can do that,” says Stell, “and

that’s why sometimes our pit bull type kiddos wait longer to find their

home.”

In the South Valley neighborhoods they canvass together on

anti-cruelty sweeps, nearly all the dogs helped by NMDog and the

Bernalillo County Sheriff’s Office are pit mixes, says Lt. Andi Taylor.

“People get them because they think it gives a personification of

toughness, so they try to make the dog tough,” adds Taylor, a pit bull

owner, “when they are actually the sweetest dogs who just want to please

their owners.”

The dogs proliferate, in other words, because they are easily

obtained, often unaltered, and basically have become the de facto street

dog.

INDEED, AT

Albuquerque’s three largest shelters—the municipal east and west side

shelters and nonprofit Animal Humane—pit bulls and Chihuahuas comprise

58 percent of all homeless dogs. Adopters come in both types, the

shelter directors say, those who definitely do or do not want a pit.

“It’s the in-betweens that we want to convince that it’s a really good

family pet,” says Barbara Bruin, director of Albuquerque Animal

Welfare. Income doesn’t have a lot to do with it, she says, but rather

how willing people are to believe the media.

With pit bulls among the top five favorite breeds in most states, why

would news outlets like Time persist with the idea that “the real

problem” is “pit bulls were bred to be violent”? Perhaps for the same

reason they persist in portraying certain racial or religious groups as

inherently violent, or certain sexual orientations as inherently

depraved—because it lets everyone else off the hook. While it has become

dangerous and even illegal to discriminate against humans, targeting

animals is no crime. They are legally property, to be seized and

destroyed like criminal booty—as they are in Denver.

Blaming pit bulls for the viciousness of human society helps us

“solve” intractable problems for which we all might otherwise share some

responsibility, like poverty, injustice, substance abuse, and a

cultural obsession with violence and revenge.

Animal protection groups now frequently link animal with human abuse,

tracing both to factors that lead children to grow up lacking empathy

for others. But there is nothing illogical or incongruent to a child

witnessing his first dog fight. It makes perfect sense in a society that

presents killing as entertainment, worships firepower, and loves

competition.

Someone is always the loser, any child will tell you, and it is the

one who is weakest. That’s why thousands of innocent animals who were

bred to look vicious must die to redeem humankind.