Horse whisperer’s mustang finds

new job as ‘child whisperer’

Trainer’s bad luck is good fortune for at-risk teens

Horses are used as “therapy” animals because they have a special sensitivity, some say, to human emotion. But it doesn’t require that for a teenager to identify with a wild mustang, says Pat DuBois. The teens she works with feel like wild animals themselves, torn from their homes and forced into a system of strange rules.

DuBois started introducing kids to horses while working as clinic director at New Day Youth & Family Services, a transitional housing program in the South Valley. She found that the animals had a powerful effect on them.

Now in private practice, DuBois continues to host teens from the shelter two mornings a week at her Ranch DuBois in Corrales. Through group exercises and learning to care for the horses, at-risk youth cut through the boredom of counseling and therapy, making it easier to reach the part of them that will open up and be honest.

“I first let them pick a horse,” DuBois says of her seven equine staff members. “It’s interesting which horse they pick, and why. That already tells me something.” Many of her horses have been through tribulations of their own, like being exploited by drug companies, or losing their families. Spending time with them turns out to be a powerful metaphor for the teenagers, who come to understand the importance of building trust and developing sensitivity.

“The horse is often a mirror for us,” DuBois says. “As prey animals, they are highly intuitive. Horses hate incongruency and can point it out in people.” In other words, unexpressed emotion is often expressed by a horse, which is why a seething cowboy is going to have a time of it when he goes to saddle up.

But it’s not just the kids who star in this comeback story. It’s also the horse. Sully the mustang was the horse assigned to Corrales trainer Susan Palmer when she was selected to compete in Extreme Mustang Makeover last summer. He had been rounded up by the BLM in Idaho, and Palmer had 90 days to show TV audiences how tame and trained he could become.

Extreme Mustang Makeover is both a challenge for trainers and a vehicle to get more wild mustangs adopted. Sully turned out to be a poster child in this respect. Completely new to human contact, he was docile and curious from the start—a wild piece of luck for Palmer, who had never trained a mustang before. After two months, she could lie on him, stand on him, ride him with a dog on her lap, and twirl a lariat. Sully had even learned to smile and bow.

But then Palmer’s luck ran out. The morning of the contest, she accidentally locked herself in her trailer and had to crawl through the window, falling and shattering her foot in five places. Sully never made it to the show or the auction block.

That turned out to be a wild piece of luck for Pat DuBois, who was looking for a calm riding horse for her therapy program. “I would never have thought of a 4-year-old mustang,” she admits. A friend told her about a mustang for sale right nearby in Corrales, and she watched his online video. Intrigued, she went to ride Sully, whom she found highly unusual.

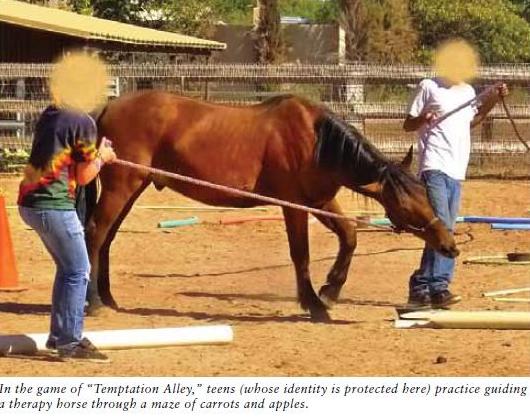

One exercise that Sully loves in his new role — since he is hugely motivated by food — is the game known as Temptation Alley. The teens create an obstacle course in the pen, placing carrots and apples where a determined horse could snatch them. Then they assign their own temptations to the obstacles, such as “partying,” “fighting with my dad,” “skipping school,” and take turns leading their horse through without letting it give in to temptation.

“It’s the process that’s important to me,” DuBois explains, when the group talks later about what happened. She asks the kids, “Who holds your lead lines?” Often it turns out they let the horse grab the very temptation that they struggle with most.

“It stays with them,” she says of the experience. “I think the visual image of what happens when your support lets go is powerful.” Identifying with the horse, the teens can start caring more for the wild part of themselves.

Just grooming the animals is therapeutic for many of the kids, who may have been hyper-vigilant their whole lives, says DuBois. Coming from an environment of violence, conflict, and substance abuse, they are unaccustomed to the peaceful high of spending time alone with a responsive animal.

“For the kids, the focus is learning to ride,” DuBois notes. “For me and my staff, it’s seeing them smile, the honesty that comes out. Then we can start to do some therapy.”

DuBois uses as her model for therapy a program known as EAGALA, or Equine Assisted Growth and Learning. One of the first programs to use horses in therapy, EAGALA was pioneered in the late 1990s by social workers at a residential treatment facility in Utah, together with a local rancher. DuBois trained in both this technique and Epona, a program taught by Tao of Equus author Linda Kohanov.

A lifelong equestrian, DuBois finds horses to be valuable partners in her work with families, Vietnam vets, and women in transition. Her six working horses include a miniature and a Tennessee Walker, plus a “rez” dog named Charlie. But “the kids all talk about Sully the mustang,” she says.

When she was training Sully in July 2011, Susan Palmer told the Corrales Comment, “He’s going to be a really good trail horse for someone who just wants to ride, or turn their grandkids loose with him all day.” The casual remark turned out to predict his fate.

Unflappably gentle, wild but wise, Sully makes an unusually appropriate role model — large enough to demand respect, but captive enough to sympathize with. “They identify with the fact that he’s not with his family,” DuBois says of the homeless teens. “Sully is learning how to be in the world. And so are they.”

'Mustang Sully'

It must be the wild horse inside Susan Palmer that tipped her off on how to train one.

With little in her bio to suggest a “horse whisperer” — the retired social worker and mother of two from Washington doesn’t even own a horse these days — she took refuge in horses as a child to escape the frustrations of being an Indian adopted into a white family.

“Horses saved me,” she says.

She remembers jumping on her horse and galloping bareback into the woods in Montana or Oregon, where her adoptive father worked for the Forest Service. Eventually she connected with other Indians and started spending time on the Flathead reservation in Montana. She married a Native man, and has spent her career working with Native populations.

When they moved to Corrales a decade or more ago, the family had two horses. Now divorced, with grown children, Palmer finds it easier to train horses without owning any.

She was drawn to the Extreme Mustang Makeover initially as a spectator. “But I’m not a good watcher,” she laughs. “I never go to [horse] clinics or anything.” She learned to ride from old-school horsemen in Montana, unheralded Buck Brannaman types, “people who just had the gift.”

When she found out the show was going to be filmed on the Navajo reservation in Arizona, Palmer decided to apply. “A horse is a horse is a horse,” she says. “Some of the worst horses I’ve been around are domestics that have been babied.”

The mustang she was given, which she named Sully because “he couldn’t be Mustang Sally,” turned out to be a dream to train. He was “naturally smart and nosy.” Even after the injury that shattered her chances, Palmer was still thinking about how he might show his stuff.

“But they were gracious,” she says of the Mustang Heritage Foundation, which put her in a training program that would reimburse her for any horse she could train and get adopted. Sully became the first candidate, and she found the “absolutely perfect” home for him at Ranch DuBois, where he didn’t have to leave the state.

Now Palmer is preparing for her next challenge: Mustang Million, a multi-event show that will place 1,000 wild horses and award $1 million in prize money next year. The commitment is a little greater this time, since contestants have to first adopt the horses they will train. But Palmer is ready. She has even chosen her event: bareback jumping. The trainer is apparently still as wild as any horse she’s planning to train.

Meet your new pet mayor: Elektra

A horse of course!

It should come as no surprise to anyone in “the Horse Capital of New Mexico” that Corrales’ top elected animal is once again equine. In fact, Elektra, a 7-year-old quarter horse, is the only horse that ran for top dog (so to speak)—against six dogs and a goat. Her campaign slogan? “Don’t let Corrales go to the dogs.”

The fact that one of the canine candidates died after a rough weekend of campaigning testifies to the rigors of the pet mayor race.

“We went to the Grower’s Market three times, Dan’s Boots, Paul’s Vet, the Village Merc—all on horseback,” said the mayor’s spokeswoman, Kathryn Sikorski. Between appearances and fundraising, Elektra and her campaign staff found the race to be a big commitment, as it also meant updating social media sites, crafting campaign materials, and hitting up fans in the American Competitive Trail Horse Association (ACTHA), where Elektra has competed nationally.

Their efforts proved worthwhile, however, when Elektra alone accounted for more than half the $2,646 raised for nonprofit groups in Corrales. Last year, too, the two horses competing in the Kiwanis Club fundraiser raised the lion’s share of money—$2,200 of the $7,879 total—in dollar-donation “votes.”

“Maybe horse owners are more generous,” Sikorski ventured. “They tend to give $10 or $20 instead of $1 or $5.” The runner-up goat raised only $268.

Through her spokeswoman, the pet mayor graciously gave her first press conference in office.

How did the campaigning go?

She held up well. It was five weekends, and we did something every weekend, sometimes both days. She would meet-and-greet people going in and out of the stores, sometimes let them feed her treats. (She got spoiled.) The thing that was most appealing was the children and old people. All the kids wanted to pet her.

Why did she win?

She raised the most money! She had a Facebook account, Twitter (though only four followers), and had a lot of friends contribute from ACTHA. So it was not necessarily just Corrales. But as the one horse, the dog votes were divided. And going to the feed stores, we campaigned hard.

We also went to Corrales Elementary on fair day with two of the dogs, and she did good. It was unnerving for me to see that many kids, like 12 classes. But she got to learn that kids mean petting. I like being an ambassador. And she is happy to stand there.

Did (former pet mayor) Aspen leave big horseshoes to fill?

Yes, because Aspen did so many things. She was involved in so many events, and wrote a column in the Corrales Main Street News.

What are Elektra’s goals?

The main thing is to promote the horse culture of Corrales — getting people who are not horse people to see the value of horses. Because it is the Horse Capital of New Mexico.

Does she have any other races coming up?

On the competitive side, we will continue to do trail rides and cow-pushing. We got to ride with (vaquero horseman) Martin Black, that was a big deal — got to back a cow into a bulls-eye. I want to make her a bridle horse. That’s where you’re using a spade bit, and you don’t use your hands. The process takes five to seven years, and we’re just starting. It’s more like a skill, or a spiritual thing.

And she is continuing to mature. She has been in parades before, but being in the Pet Parade with the band — things like that improve her skills. It tends to make a horse more confident.

Whatever we do, pet mayor or trail riding, we like to win!