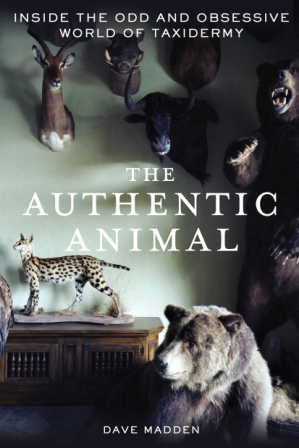

By Dave Madden

From The Authentic Animal

by Dave Madden. Copyright © 2012 by the author and reprinted by

permission of St. Martin’s Griffin, an imprint of St. Martin’s Press,

LLC.

IF THERE'S ANYTHING I've discovered about taxidermy, it’s that people can

have very extreme emotions when it comes to animals. And maybe this is

just as good a place as any to get into the ongoing debates surrounding

animal rights, for by its very nature taxidermy is an affront to those

rights. At least, this is the stance taken by People for the Ethical

Treatment of Animals. “If an animal dies of natural causes,” Colleen

O’Brien, PETA’s director of communications, told me, “PETA would not be

ethically opposed to his or her body being preserved by taxidermy,

although it strikes us as disrespectful to put the animal on display.

We’d never preserve and display a beloved human family member.”

Indeed. PETA’s ethos is a golden rule variant. This is the way taxidermy

is disrespectful—we wouldn’t allow it for one another. All the

taxidermists I’ve talked with, naturally, disagree with PETA. They see

taxidermy as a chief form of respect for animals. Like Wendy

Christensen-Senk, the chief taxidermist at the Milwaukee Public Museum.

Yes, she loves taxidermy, but it cannot compare to the act of bow

hunting elk, her favorite quarry. It’s not what most people think when

they think of hunting. An arrow can go only a fraction of the distance

of a bullet, and so it’s not sitting up in a tree and listening for the

footfalls of something tiny and precious. Elk are animals larger than

most Volkswagens, and when they run it sounds like a fleet of horses at

the finish line, and for Wendy the only way she’s going to come out of

this with a kill is to run right alongside these animals, all of them

bugling their guttural squeals over the thundering of their hooves.

“There is literally nothing more exciting in the world,” she says,

likening it to a religious experience. Of every kind of animal on the

planet Wendy loves the elk the most. She tries to hunt one every year.

Like most contradictions, it’s one we’re uncomfortable with, and that

characterizes what environmental scholar Stephen R. Kellert calls

“nature hunters”: people who love and admire the animals they hunt, who

do it for an “intense involvement with wild animals in their natural

habitats.” Nature hunters are distinguished from utilitarian hunters,

who do it for the meat, and sport hunters, who do it for the mastery and

competition. The nature hunter, more than any other hunter, felt [in

Kellert’s study] the need to rationalize the death of the animal.

Kellert found that most hunters (43.8 percent) were classified as

utilitarian, with sport hunters falling in second place (38.5 percent).

Nature hunters constituted only 17.7 percent of those surveyed. But this

is the demographic that almost every taxidermist I spoke with would

place himself or herself in. For what other reason than affection and

admiration for wildlife would a person become a taxidermist? Certainly

not the money. “I have an extreme love for wildlife,” Wendy says. “I’ve

always had one. When I was young it always bothered me to see animals

all destroyed on the roadside.

Here, then, is a kind of respect for animals. This animal was alive;

then it died. Let’s make it look alive again. One major element of

taxidermy is the way it broadcasts human dominance. We can do this to

animals, but they can’t do this to us, which brings us back to PETA’s

original complaint. The question of course is who gets to decide what’s

best for animals, and what exactly does that entail?

If there’s anyone on the planet best qualified to speak for animals,

it’s the bioethicist Peter Singer, if only because he seems to have

taken the most time to think about it. In his Animal Liberation—the

PETA bible, in many ways—Singer lays out the case for the equal

consideration of animals and the minimizing (if not the end) of animal

suffering. Singer’s approach is rational, not emotional. He admits early

on to not being particularly interested in animals, or even loving

them. He “simply want[s] them treated as the independent sentient beings

that they are, and not as a means to human ends.” Singer smartly avoids

claiming that he knows what’s best for animals. He just knows what’s

bad for humans and humans’ ethical living. “Speciesism” is as ethically

wrong as racism or sexism, and because we would never sit back and allow

suffering on other humans we should also reject the same kinds of

suffering done to animals.

Singer’s focus on suffering is where his ideas begin to overlap with hunting. Rare is the hunter who disregards animal suffering. Rare is the hunter who isn’t concerned for the conservation and proliferation of game. Hunters and animalrights activists have tons of basic, fundamental stuff in common, but what gets broadcast is “meat is murder” and “you’ll pry my gun out of my cold, dead hands.”

I've never felt much fury or even held any mild criticism toward

hunters. I’ve also never understood the impulse. But what have I ever

known about animals? I know that the truth of this world is that our

capacity for love is large enough to allow some room for animals, and

yet this allowance isn’t as warm as our love for other people. It’s

colder, darker, and full of bloodshed. For many people this love has

lots of capacity for cruelty. We keep our dogs in cages throughout the

workday because, we rationalize, they enjoy having a small, tight space

all their own. And when it comes time to sleep at night we do it pretty

soundly. Likewise, many people go out in the wild and find animals to

shoot and kill, and their nights are just as restful. They’re not

monsters. They don’t lack empathetic skills. Moral equivalence isn’t

anything I know much of. But increasingly these days, as I talk to new

kinds of people, it’s getting harder and harder to confidently call

something out when I see it as “wrong” or “immoral.”

Hunting is not taxidermy. The latter can exist without the former. But

more often than not taxidermy is an outcome of hunting, and so it’s

seemed disingenuous to talk so freely about taxidermy without

acknowledging its grisly, ethically murky cousin. If it’s true that

hunting can be (but isn’t necessarily) a way to honor an animal, or that

tangential to the act of hunting is a respect and love for the animal

being hunted, then it follows to me that taxidermy is probably the best

way to broadcast this love to a dubious audience. Because if you shoot a

deer and dress the carcass and butcher the meat to feed your family

through the winter and take the skin and make something of it, isn't

this a form of honor, of deferential respect?

We make icons of our idols, and we have done this since Lascaux. It’s

why self-conscious, eBay’d taxidermy is, in the end, such a drag to find

in people’s houses. An animal had to die for this? To outfit a TV room

with a retro-chic vibe? And I say this as a man who has purchased and

hung self-conscious eBay’d taxidermy. But no longer. Let this be a bit

of advice for anyone looking to get a game head: Don’t just get the

mount, get the story behind the mount. Talk to the hunter and listen to

the steps he took to track down the animal and shoot it. Figure out what

happened to the flesh, the bones, the rest of the skin you’re not

seeing. Maybe it uncomfortably reminds us that this thing we have

decorating our homes had its life taken from it, but more than anything

it keeps taxidermy honest. Every mount is an encounter, a chance to

engage in an animal that would have otherwise been a stranger to you.

It’s why we invented epitaphs: None of us wants to be forgotten in

death. We can’t ever know whether animals feel the same way, but doesn’t

it seem respectful to assume so?