Documentary explores 'deadly link'

of family violence

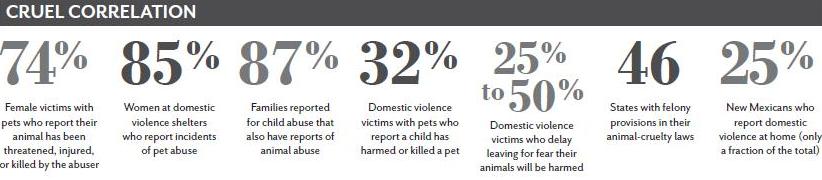

New Mexico may rank at the bottom of many national measures, but not when it comes to animal abuse. Our state is among the five kindest to animal abusers, according to the Animal Legal Defense Fund.

Not coincidentally, New Mexico also harbors a fair share of domestic violence. According to 2010 data on gun violence from the Center for American Progress, we rank seventh among states for women killed by men, and seventh for children murdered with guns.

Statistics like these are nothing to be proud of, which is why former educator Nina Knapp has devoted herself to

Sherry Mangold of Albuquerque’s Animal Protection New Mexico visits

classrooms to teach compassionate animal care. She often brings Sophie,

an Italian Greyhound who was stabbed in a domestic violence case.

a documentary film project called The Deadly Link. Funded largely

by online donations and film professionals willing to donate their time, the feature-length documentary has progressed in fits and starts, through the tenacity of Knapp and co-producers Angie Beauchamp and Sheryl Brown. Launch is now set for November.

Their goal is to air the film on television, to reach the widest possible audience with the message that animal abuse often means humans are being victimized—and vice versa. While this connection is already well represented in the media, what needs to be better connected, says Knapp, are people who might see signs of trouble with people who can help.

Fortunately, New Mexico does rank near the top in making those connections. Thanks to programs like the 2012 conference “The Link Between Animal Abuse and Human Violence,” funded in previous years by the state (and last year by the ASPCA), agencies such as police, shelters, animal rescue, and animal control “are learning how to address the pet aspect when they go into a home,” Knapp says.

In Bernalillo County, for example, a collaborative effort between the Animal Care department and County Sheriff’s Office known as PET (Pro-active Enforcement Team) allows for joint actions where deputies see either animals or humans at risk. The two offices also work together patrolling trouble areas.

And while it is tricky to get families to testify about domestic violence, animal abuse can often be documented and prosecuted, so violators end up behind bars. That’s why making those connections is important, says Knapp. From meter readers to mailmen, veterinarians, schoolteachers, and neighbors, many people are in a position to alert some agency to intervene.

The “deadly link” connects multiple issues: not just domestic violence and animal abuse, but also elder abuse, bullying, self-mutilation (“cutting”), and criminal activity such as drug trafficking, DUI, rape, and homicide. Any one of these components greatly increases the chance of finding the others—which is why police departments have become interested in animal abuse.

The common factor, says Knapp, is a family cycle of violence, where children grow up without a sense of empathy. Teachers and parents know that empathy does not always come naturally to children. “You have to tell children to be nice to pets, not to be so rough with the new baby,” Knapp observes. In families where children grow up instead with normalized violence, they often “act out,” victimizing those who are weaker. As parents, they perpetuate the cycle.

The Albuquerque-based advocacy group Animal Protection New Mexico (APNM) has since 1999 run a network of “safe havens” for victims of domestic violence who need help sheltering their animals. Known as CARE, or Companion Animal Rescue Effort, the program maintains a confidential list of individuals, businesses, and agencies that will step in and help look after the animals.

The program’s Alan Edmonds says he ends up handling about one case a month. Recent examples include a teacher whose concern about a child led to alerting not only animal control, but also police and child protective services. A worse case involved sexual abuse of both family and pets. “The mom and children and animals all managed to get out and get the help they needed,” Edmonds said, but “the animals ended up being adopted out, and they had such severe emotional and socialization problems, they couldn’t be adopted out to just anyone.”

Sherry Mangold, APNM’s educational outreach director, got her therapy dog Sophie through the CARE program. The Italian Greyhound had been stabbed in a domestic violence case. Unable to pay the resulting veterinary bills, the victim asked Mangold to adopt and train Sophie as a therapy dog. The two now visit middle schools as part of Mangold’s ten-week curriculum on animal care and responsibility.

Mangold believes teaching children to recognize animal abuse is the first break in the link. Edmonds agrees. “If you want to make a kid a sociopath,” he says, “get him to train a pit bull puppy to fight, and make him kill it when it loses. There you go—you have a time bomb, a person who won’t have concern for people or animals or anything.”

Unfortunately, in some communities, blood sports are a family tradition, he says-and so is domestic violence. The difficulty of bringing such situations to light becomes clear to anyone who tries to find victims to interview. Knapp ended up relying on women who approached her with stories about their past.

Dismal as such stories may be, the filmmakers also wanted to focus on solutions. Knapp hopes to bring a film crew this summer to the Rose Brooks Center in Kansas City, Mo., one of the first shelters in the nation to accept pets.

“A few years ago, a woman came in with her Great Dane, which they couldn’t take,” she explains. “And she wouldn’t stay without her ‘angel.’” It turned out the dog had laid across the woman and taken most of the blows as they were both beaten with a hammer.

Such stories highlight the incredible power of the human-animal bond—which Knapp sees as the light being shined into the darkness. “The animal may have been their only refuge,” she says of people hurt by those closest to them. “How do you walk away from that?”

Donate to the film fund and follow the project on Facebook. Or contact the producers.