|

Modern art famously shattered longstanding conventions of representation when abstraction burst onto the postwar art scene

as the ne plus ultra of pictorial radicalism. A few decades later, modernism itself was being snubbed by a postmodern

art that mined garbage cans and Old Masters alike for media as debased as lard and elephant dung to mount beside crucifixes

and sorrowing Marys. Still, nearly two decades after Andres Serrano's Piss Christ pushed the outer limits of artistic

freedom, the history of art remains silent on a 500-year-old Spanish figure sculpture tradition that one art historian has

called unassimilable into the canon (McKim-Smith).

These life-size wooden sculptures of the Virgin Mary and flagellated Christ, realistically rendered and adorned with real

clothing, glass eyes and tears, wigs, and gangrenous wounds caked with coagulated blood, have suffered "a problem of medium

for several centuries,"; as McKim-Smith puts it mildly. The reasons for this oversight, comprising hundreds of highly valued

pieces by recognized maestros, cannot be attributed to the sculptures' religious or graphic nature alone, as any survey of

Western art history will prove. McKim-Smith points to sculptural canons that originate with the history of art itself, especially

the 16th-century prejudice toward models from ancient Greece. Favoring monochrome marble and bronze set up a contrast between

"the barbaric art of the Gothic North and the superior civilized art of the Greco-Roman South, or the Italian Renaissance,"

and was taken up eagerly by the Roman Catholic Church as ammunition against the Protestant Reformation (McKim-Smith 15). By

the late 1500s, painted or polychromed wood — the most widespread cultural medium in Europe since the Middle Ages —

had fallen out of favor in central Italy, the capital of art patronage through the 17th century (Stratton 5).

With foundational 18th-century art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann, critical writing began to promote what were believed

to be the formal qualities of classical figure sculpture, such as "Noble Simplicity and Tranquil Grandeur" (McKim-Smith 18),

reflected in ideals of order, proportion, harmony, and balance. "As white is the color which reflects the greatest number

of rays of light..., a beautiful body will be the more beautiful the whiter it is," Winckelmann wrote in 1755 (qtd. in McKim-Smith

18). "It followed that sculpture should not be painted," says McKim-Smith, "and painting should not be sculptural.... God

had been secularized and Taste had been deified in Germany, Italy and France, but in Spain sculptures ... still manifested

bright paint, crystal tears, ivory teeth, real clothes — and ornamentalized emotion". At a time when European art standards

were being set, in other words, the Spanish polychrome tradition was already irrelevant to any but Spanish critics.

As one of the few art historians outside of Spain who has written on Spanish wood sculpture, Gridley McKim-Smith traces its

"critical misfortunes" not only to its religious subject matter and discredited media, but to its investment in "vernacular

religious behaviors that themselves express acute and perilous experience" (22). It is worth recalling that the pinnacle of

Spain's polychrome tradition, the 15th- to 17th-century Golden Age, coincided with the Counter-Reformation, the Inquisition,

and the Baroque, a period of great religious fervor in which Spain played a major role in the Catholic Restoration. Historian

Stanley Payne points to the Iberian peninsula's long history of confrontation with invaders and internal threats — from

Moors to Protestants to a prosperous Jewish minority — for the elaboration of a militant, xenophobic orthodoxy that

he characterizes as the highest development of medieval Catholicism (25-6):

"The principal effect of the Islamic confrontation with Hispanic Christian society was not any orientalization of that society

but rather the development of a distinct Hispano-Christian subculture within western civilization ... whose attitudes and

values were shaped ... by a centuries-long process of warfare and confrontation. This resulted in a kind of exaggeration of

typically medieval qualities in Hispanic culture.... a more extreme and narrow form of a common phenomenon" (23).

The late 15th and 16th centuries saw rapid growth of religious intensity and evangelism in Spain, but this was hardly of the

doctrinal variety; beyond the observance of basic rituals, religion for most people formed part of a complex of identity that

united Catholics against the internal menace of Lutherans, Moors, Gypsies, and especially converted Jews (Rawlings 79, Payne

45-6). Until about 1600, the Spanish countryside was not well served by priests (Rawlings 79), and popular religious feeling

manifested primarily through explosive growth in religious confraternities. A city of 10,000 might have 100 of these lay brotherhoods

that governed daily religious practice and thus posed a growing threat to the Church (Payne 45). By the late 16th century,

the ubiquity of these tightly knit groups led to repeated regulatory campaigns under the mandates of the Council of Trent.

It is at this disjuncture between doctrine, practice, and belief that flowered most notably in Golden Age Seville, I think,

that we have to examine the art historical "peril" posed by Spanish religious sculpture, the archetypes of which are paraded

through the streets during the eight days preceding Easter in a mass re-enactment of the Passion of Christ. In the "structures

of feeling" (Williams, 128-35) to which these carnivalesque events give vent, we find a unique expression of Christianity's

instabilities, its ambiguous relationship to visual imagery, and the skeletons in the closet of art history itself. By examining

the makeup of Europe's neglected sculptural stepchild, in other words, we get a mirrored look at the underside of what we

call art, and what had to be rejected or ejected in its naming.

I WILL TAKE the polychrome religious sculpture of Seville as a prototype, because the Andalusian city houses many of the masterpieces

of the genre, which continue to be processed at Semana Santa, or Holy Week, in a street spectacle on a par with the Rio de

Janeiro Carnival. One can hardly overstate the importance of this week in the Andalusian calendar, according to Timothy Mitchell,

who has made a career of studying its many aspects. Holy Week processions in Europe date to the fourth century (Webster 145),

but it was in Golden Age Seville that they reached their apotheosis, with scores of confraternities parading their sculptures

on elaborate narrative floats, accompanied by armies of penitents and other hooded marchers, in former times whipping themselves

to draw blood or carrying heavy crosses barefoot to the cries, sighs, tears and emotive recitations of poetry from the crowd

(Mitchell).

The confraternities of Andalusia developed the variant of polychrome wood sculpture that is designed to be clothed, the imagen

de vestir. These were articulated only in the parts not hidden by clothing, often jointed to allow for dressing and posing

in narrative settings, and meant to be viewed in the round, in motion (Webster 59). The polychromy was done by expert painters,

with a high premium placed on lifelike renditions of flesh and wounds, often the work of specialists (Kasl). The most revered,

if not the most numerous, processional sculptures were of the crucified Christ and grieving Maria, the Mater Dolorosa.

At the sight of these figures in procession, viewers would erupt in displays of emotion and devotion that drew increasing

censure from Spanish bishops in the 16th and 17th centuries (Webster 45). Little attempt had been made to control popular

religious practice until then, but Council of Trent reform efforts included standardizing the liturgy and the teaching of

doctrine (Rawlings 80) — as well as regulating such aspects of the Holy Week processions as sumptuously dressed madonnas

and overenthusiastic flagellants, practices cultivated in the context of the lay brotherhoods. For the most part, however,

"the power generated in the processions lay fully within the control of the people" (Webster 187).

The Church could hardly eradicate such practices, in any case, given that it also promoted the use of imagery, drama, and

other techniques of immediacy under Trent to arouse popular devotion, in conscious opposition to the stoic tenor of Protestantism

(Rawlings 92). So despite the clear and growing danger of interest in mystical visions, adoration of images, and street liturgy,

the post-Tridentine Church reinforced the importance of such practices even as it tried to control how they were used (Webster

181). This accounts for some of the artistic fascination in the Baroque for illusionism and trompe-l'oeuil techniques

in the service of fostering viewers' amazed belief, such as paintings that appear to be sculptures, architectural elements,

or to open out to the sky (Stoichita 68). Likewise, Caravaggio's foreshortened limbs that seem to burst out of the picture

plane, or the mysterious reflections in the work of Diego Velazquez, implicate the viewer into the space of the image in a

way that grows perilous when no longer stopped by the flat surface of the canvas. Small wonder if the era was rich in reports

of statues weeping or climbing down off the cross to kiss a devout worshipper — though such claims were rigorously tested

by an Inquisition-era church alert to the dangers of losing control over religious experience (Stoichita 25).

While the Church had long considered visionary experience to be somewhat suspect, it began to exploit visionary idioms after

Trent, commissioning a growing number of works that would make the "invisible, visible" in the service of strengthening Catholic

piety (Stoichita 18). Paintings that dramatized biblical narrative with chiaroscuro lighting in the depiction of visions

and miracles — together with such models of piety as the image-loving Spanish mystic Teresa of Avila — drew clear

parallels between illusionistic art techniques and theophanic experience. The "poetic of the holy trompe-l'oeuil,"

as Victor Stoichita calls it, represented a new aesthetic that not only tended to cross the boundary between two and three

dimensions, but also to invite "the visionary effect" (Stoichita 70): "quasi-physical communication" with the divine image

through the medium of the gaze (Stoichita 159). Indeed, Webster concludes in her analysis of the Holy Week processions that

"the power of emotional response and devotion to the image allows a dialogue to take place between God and the faithful ...

that is mediated through the image. The more fervent the devotion to the image, the more completely God hears and understands

supplications, and in turn, the more willingly He responds by bestowing graces and mercies through the medium of the image"(185).

Processional sculptures become fully "activated" only in motion through the crowd, Webster says, where they enter the spectator's

space and time in a kind of exemplary Baroque drama that merges the present with the eternal, the material with the spiritual

(58-9).

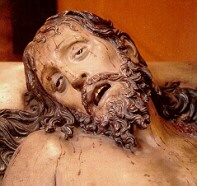

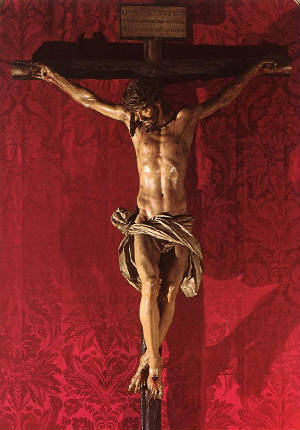

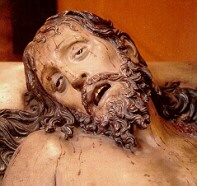

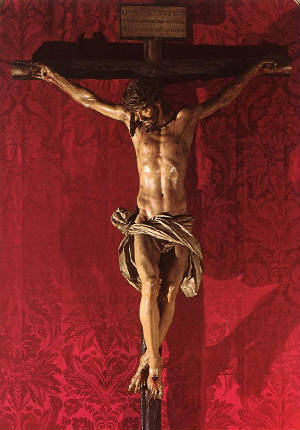

Here, then, stands one aspect of the works' "dangerous destabilization for the conditions of viewing" (McKim-Smith 22) —

even in the context of Baroque art and especially with the distance of history. For we are in the realm of an ambiguity linking

mystical and erotic experience that is far more safely aestheticized in canonical Baroque sculptures such as Gianlorenzo Bernini's

marble Ecstasy of St. Teresa. On closer examination, Bernini's Teresa experiences the divine through a superfluity

of visual codes; her body consists of voluminous, swirling draperies that abstract her inner experience (Wittkower 9). By

contrast, McKim-Smith offers Gregorio Fernández' Reclining Christ, "[w]ith its battered yet beautiful body and its

necrophiliac exaltation of death" exposing the spectator to "the danger of a sadomasochistic catastrophe." She continues:

"The eroticized violence inherent in the naked reclining Jesus has always been there as a repressed subtext of the Passion...

but the Cristo yacente now has allowed it to become unacceptably overt.... Fernández' male Venus is dead, yet his half-open

eyes are paradoxically aggressive, seizing control of the gaze in an exchange that subverts the notion of the noble vitality

of the human body..." (22).

Absent the distancing effect of canvas, marble or bronze, Spanish polychrome sculpture crosses unacceptably between the real

and the represented, endangering the "safe encounter that guarantees an experience controlled by the viewer" (McKim-Smith

22).

This is what it was meant to do, of course. The Church in Spain dangerously disturbed the animistic topsoil from which it

arose when it opted to promote representational imagery as integral to Christian devotion. Although it stopped far short of

allowing that paintings or sculptures could be "inhabited" by the divine, in rural Spain this belief had persisted for centuries

(Webster 186). Popular piety took the form of venerating a pantheon of local saints to serve as intercessors with the divine.

Events were seen as resulting from God's wrath or beneficence, so that both misfortune and grace might be interpreted as a

call to build a shrine, mount pilgrimages, or otherwise invest in protection from divine wrath (Rawlings 89-91). When calamities

grew more severe — such as the two devastating plagues of the 17th century, amid a climate of war and acute economic

depression — appeals rose to universal patrons (Rawlings 93, 127-8). The Church had long made use of such practices

to cultivate devotion to the Virgin Mary, for example, as the archetypal mother goddess transformed into a "particularly powerful

link between the local and universal church" (Rawlings 93).

It seems useful therefore to look more closely at the evolution of the two figures most heavily promoted by the Church for

worship in the post-Tridentine period — the Christ and Mary of the Passion, the most frequent subjects of Golden Age

painting, sculpture, and divine visitation (Stoichita 12; Mitchell 1) — for a deeper sense of the aesthetic "peril"

posed by Spanish processional sculpture. As Julia Kristeva has pointed out, the inner history of the Virgin Mary, for one,

speaks far more clearly to symbolic social structures reflecting primary processes of individual development than to her sketchy

historical data in the Gospels ("Stabat" 314-22).

Kristeva links individual to social symbolic development in the notion of the "abject," or what the subject must "thrust away"

in order to become a stable self. For the pre-Oedipal child, the abject is the surface of the mother's body, the prelingual

terrain of milk and tears. Before the child acquires language and enters the symbolic order, only pleasure and pain distinguish

inside from outside, Kristeva says. Differentiating pain as that which must be thrust away establishes a border, and "amounts

to introducing language, which ... founds the separation inside/outside" (Powers 61). This expulsion — to which

she traces our lingering horror of substances that threaten the unity of the self, such as blood, shit, rot, and corpses —

establishes the abject as neither part of the self nor entirely separate from it. As the ground of being, it continues to

offer the compelling fascination of both dissolving and reaffirming subjectivity — hence the can't-look-away thrill

of gruesome scenes of violence. "[J]ouissance alone causes the abject to exist as such. One does not know it, one does not

desire it, one joys in it. Violently and painfully. A passion" (Powers 9). The jouissance comes, of course, in the

temporary dissolution of boundaries between self and world, as in erotic or mystical union — the experience Kant

marked off as the sublime, a reverberation between being overwhelmed and feeling the ego's persistence against the threat.

"The abject," Kristeva writes, "is edged with the sublime" (Powers 11). It is associated with the mother symbolically

on two levels: She abjects the child, who must then abject the mother to enter the symbolic order.

At the level of culture, too, Kristeva theorizes a genealogy of the Virgin Mary as "the tremendous territory on this and that

side of the parenthesis of language" ("Stabat" 323), patriarchy's expulsion and marginalization of the archaic power of the

maternal. Through the doctrine of Immaculate Conception — the idea that she was, like her son, conceived and died without

sin (advocated with great fervor in 17th-century Spain), Mary is similarly deprived of death "based on a simple logical relation:

the intertwining of sexuality and death. ... [O]ne cannot avoid the one without fleeing the other" ("Stabat" 314). This was

Christianity's salve, then, as Kristeva sees it, soothing the "social anguish" of the male while granting the female an equal

place in her access, as mother, to eternity: Mary would henceforth be the oceanic totality of woman and God, fount of humanism

and sensitivity, a melding of the courtly Lady and holy mother "as accomplished as it was inaccessible," the pagan goddess

neutralized (and neutered) as the eternal maternal receptacle that — like the abject — would form the ground for

the coherent Christian subject, the Christ. Signs of this transfiguration abound in the nearly indistinguishable sculptures

of the Dolorosa, as passionately worshipped by their individual confraternities as they have remained "monotonously

alike" through the centuries (Mitchell 169, Webster 91-2). Decorporealized in processional sculptures that (like Bernini's

St. Teresa) articulate only head, hands, and sometimes feet, she corporealizes the conflict between being and becoming

"a continuous separation, a division of the very flesh" out of the immutable "central tree" (Kristeva, "Stabat" 324) of motherhood.

In his study of the passional culture of Golden Age Spain, Mitchell finds signs of a lingering medievalism in Andalusia's

lyric poetry, folklore, street liturgy, bullfighting, and strong psychosexual identification with a confraternity's "parental"

icons (113). While I would not so easily assign "the lower-class men of southern Spain" to being sexually repressed because

of "their lack of political autonomy, their stress-provoked fatalism, their obsession with genitalia, their depersonalization

of women, and their phenomenal devotion to the Virgin Mary" (38), I think Mitchell does unmask key meanings of the Christian

icon in observing that the Holy Week narrative glaringly omits the Resurrection. In most of Andalusia, no attempt has ever

been made to include a Risen Christ in the processions, while ecclesiastical attempts at redress were often abandoned out

of an embarrassing lack of interest (165). Mitchell proposes that the truncated romance ends instead deliberately with the

Passion of Mary, who is "nailed to the cross with her tender heart and all her being" and "left to sorrow eternally" (166,

177). Typically the processional Mary is sculpted with a sword piercing her breast, an abbreviated reference to the Virgin's

"Seven Sorrows" (Webster 93). Mitchell notes: "[T]he whole point of the Mater Dolorosa is to preserve redemptive suffering.

Someone must take up the torch of suffering that Christ passes on.... In Passional context, the Purisima can purify

sinners because she is capable of infinite pain.... Without Maria, there would literally be no limit to rough Patriarchal

justice" (177-8).

Devotion to the image of the Mater Dolorosa has thus evolved along lines parallel to the ideal response to the tortured

Christ: tears emanating directly from the heart as visible evidence of "an intensely painful sorrow for sins committed, for

having offended God" (source?). Tears in contemplation of the Passion were believed to purge one's sins, "and in Spain this

was the great spiritual exercise of the sixteenth century" (Christian 97-111). Milk and tears, "privileged signs of the Mater

Dolorosa," are what Kristeva calls "metaphors of nonspeech," prelinguistic aspects of the abject. "The Mother and her

attributes, evoking sorrowful humanity, thus become representatives of a 'return of the repressed' in monotheism" ("Stabat"

322).

Full-blown devotion to the pain-stricken aspect of the Virgin — including the singing of saetas, lyrical songs

composed for the occasion (Mitchell 82) — is among a number of ways that popular religion in southern Spain, expressed

in the multimedia spectacle of the Passion, emphasizes those aspects of Christianity that seem at once to comprise part of

its inner history, and must thus be repressed time and again by the Church. For passionate investment in the figure of the

Dolorosa means entering into the experience of division that she represents, "the anguish of maternal frustration"

(Kristeva, "Stabat" 322) — a kind of will to power that longs after the lost eroticism (of which tears are the sign)

of her son's unique, categorical death (ibid.). Cries and anguish, tears, the singing of saetas, the extravagant, superfluous

adornment of the Dolorosa statues with gifts of finery and jewels, all seem to suggest this experience of longing after

"the wholly masculine pain of a man who expires at every moment on account of jouissance due to obsession with his own death"

(Kristeva, "Stabat" 323). Any who experience Holy Week processions or view its sculpture must feel this aspect of its aesthetic

(if it can be called that): Their impact is difficult to "put into words," for it exploits the boundary between speech and

its opposite, a lapse into pre-rational silence and tears. The post-Tridentine Church showed its discomfort with such evocations

in its attempts specifically to regulate the comportment of flagellants and realistic adornments to religious sculpture (Webster

118-20), as well as in its general inability to incorporate even virtuoso works such as Juan Martinez Montanes' Jesus de

la Pasion into its artistic heritage (McKim-Smith 16).

THE FIGURE OF CHRIST as worshipped in Spain goes even further in emphasizing the erotic aspects of the sacred. Not only is

the nearly nude figure of the Crucifixion sculpted as beautiful, young, and desirable, but everything about it speaks to death

in a ghastly, corporeal way, making the coincidence of sensuality and death implicit in the Passion scandalously explicit.

I find it helpful here to apply Georges Bataille's figuration of the corpse as central to "obscenity" (not unlike Kristeva's

"abject") to name "the uneasiness which upsets the physical state associated with ... the possession of a recognized and stable

individuality" (Bataille 17-8). According to Bataille, the gulf between human beings is tantamount to death. As discontinuous

beings — unlike amoeba that reproduce by splitting and thus traverse a microsecond of continuity — for us continuity

equals death, and presents the dizzying, seductive prospect of return to the state from which life arises (13). That is why,

Bataille says, the primary taboo on violence and all its aspects — murder, blood, corpses — must be regulated

by structured occasions for its transgression, such as blood sacrifice. The ordering of transgression enables human work and

productivity while maintaining psychosocial equilibrium. The important point here is that "[t]he frequency ... of transgressions

[does] not affect the intangible stability of the prohibition, since they are its expected complement" (65). Under this schema,

the sacred is simply what is taboo, which in pre-Christian societies could be what Kristeva calls abject, as part of a system

delineating the sacred and profane. The awe inspired by the prohibition later evolves into what we call religious feeling,

as "[m]en are swayed by two simultaneous emotions: they are driven away by terror and drawn by an awed fascination" (Bataille

68).

Christianity transformed this stable structure, Bataille proposes, by banning transgression in hopes of overcoming violence.

Whereas pagan religion is based on transgression, and defines the sacred by the taboo, Christianity rejects transgression,

blocking its access to the sacred (120-1). Instead it erects a god who is at once discontinuous and sacred, whereas death

is no longer equated with continuity but with eternal prolongation of the discontinuous soul. What gets lost in translation

is "the path that led from isolation to fusion, from the discontinuous to the continuous, the path of violence marked

out by transgression" (120-1, emphasis mine) — the very path that is revisited symbolically, it seems to me, in the

Holy Week processions, which are closer to the inverted world of pagan feast days than to the liturgy of the reformed Catholic

Church.

Not content to contribute to the Christian sacrifice solely through the subjective experience of sin, the Andalusian faithful

embrace the primordial guilt of desiring the violence of sacrifice, as in the unique Spanish tradition of the bullfight. Transgression

is announced through the Holy Week hungering after a state of anguish, the emphasis put on abjection in contrition and tears,

the general will to dissolve the boundaries of ego in the context of piety. Bataille and Kristeva both link the state of anguish

to death, as a feeling that approaches death in hopes of transcending it. For Bataille, this is accomplished partly by violating

the taboo: Anguish announces the taboo and accompanies the transgression (38, 87). For Kristeva, "the unthinkable of death"

is answered by maternal love, felt as "a surge of anguish at the very moment when the identity of thought and living body

collapses" ("Stabat" 327).

In fact, the Spanish "cult of death," so often remarked now in its Mexican variant, first became prominent in the 17th century

(Payne 56). As late as the 18th century in Andalusia, Mitchell says, the population fixated on dying "with an eager, almost

impetuous attitude, entirely devoid of ... squeamishness" (source?). In the presence of corpses they showed none of that "hurried

movement to occult the cadaver, which was common north of the Pyrenees"; instead, women were known to throw themselves on

the deceased and display "a tactile relationship with the lifeless body of uncommon intensity" (qtd. in Mitchell 73). As Bataille

notes: "The taboo which lays hold on the others at the sight of a corpse is the distance they put between themselves and violence,

by which they cut themselves off from violence" (44). In its unleashing of passions implied and never fully contained in Christianity,

the Andalusian devout define the Christian paradox as did witches' sabbaths, which "made clear what Christianity concealed,

that the sacred and forbidden are one, that the sacred can be reached through the violence of a broken taboo" (Bataille 126).

At the same time, participation in the abject is modulated by the figure of the decorporealized Mater Dolorosa, who

"obstructs the desire for murder or devouring by means of a strong oral cathexis (the breast), valorization of pain (the sob),

and incitement to replace the sexed body with the ear of understanding" (Kristeva, "Stabat" 329).

IT IS IMPORTANT to bear in mind that this testing of social and psychic structures during Holy Week takes place through

the processional icon — not only in terms of what it represents, as a marker or symbol, but also in its status qua

sculpture. It is not just that the Crucifixion represents a corpse; as a realistically painted doll, the sculpture symbolizes

death on a more profound level, which Freud referred to as "the uncanny" (121-62). Briefly, Freud attributed the strange,

haunting feeling we get around both dolls and "doubles" (i.e., in stories) to their evocation of a time when the boundaries

between self and world were not clearly defined — a feeling that for adults amounts to death. In her study of uncanny

doll images in the work of Freud and Rilke, Eva-Marie Simms elaborates: The child responds to the doll emotionally as if it

were alive, until at some point its silence and unresponsiveness give rise to rage, propelling the child into assuming her

own separate identity (671). This corresponds to the formative transition from primary masochism (the death instinct) to externally

focused libido, a potentially sadistic will to power that turns destructive if left unchecked. With this transition, pre-Oedipal

masochism goes underground as a repressed part of the psyche (e.g., as the abject), and makes itself felt in an uncanny regression

around the doll/corpse/double. In Rainer Maria Rilke's gruesome stories about dolls (which the German poet confessed to abhor),

"[t]he doll, experienced in itself and apart from the world of play, reveals that there is a limit to life, that brute matter

cares very little for human feeling, and that death is everywhere. It also shows that our involvement with the material

stuff of the universe constitutes its meaningful structure" (Simms 676, emphasis mine).

I would like to suggest that there is in the Holy Week devotions something of Rilke's rage against the doll "for failing to

fulfill its promise of warmth and companionship" (Simms 675). Inviting regression, the doll/double provokes a projection of

masochistic anguish over separation from the maternal that is then safely expiated in the transgressive violence of the Crucifixion.

Uninhibited crossing between narcissistic immersion and self-affirming rejection; love and murder; union with the mother and

identification with the father, is finally resolved in the Christian transcendence of death in a triumph of the discontinuous

self, or ego. This movement across the permeable boundaries of the self serves to expose and emphasize the instability of

the Christian subject.

Externally this movement manifests as pain, exalted in Spanish Catholicism as "a cultural ideal of the first magnitude" (Mitchell

7), especially when rendered visible in tears and blood. Christianity's otherwise repressed body becomes instrumental "in

as much as it is the soul's instrument of exteriorization, and on condition that this ... presents itself as suffering" (Stoichita

174). Pain and the wound are intimately connected to abjection and death, representing the body's physical and psychic opening

to its origins. It is against pain that the self originally defines itself, and intense pain correspondingly unravels language

and obliterates the coherence of self and world; it "is the equivalent in felt-experience of what is unfeelable in death"

(Scarry 31). Theorizing pain as the source of all human "making," Elaine Scarry notes that the dissolution of consciousness

effected by intense pain remains purely subjective until the screams of torture, for example, translate it into the objective

insignia of state power (27-59). Conversely, the manmade object is a visible manifestation of the inside/outside distinction

that founds the self, a distinction based on pain (305). The manufactured object first arises as an idea in relation to comfort,

so it always contains as part of its inner history "a material record of the nature of human sentience out of which it in

turn derives its power to act on sentience and recreate it" (280).

I believe this profound connection between objects and pain is crucial to understanding the history of certain types of artifacts,

the ones we classify as art. The inner logic of objects — that they are a "making sentient of the external world&" (Scarry

281) — is normally hidden from us, Scarry says, by "the instability of our descriptive powers" and "absence of appropriate

interpretive categories" (279) resulting from the dynamics of political power. Without delving into her argument, I think

we can propose that our modern understanding of art objects constitutes one of the inappropriate categories that blunt our

descriptive powers. For no matter how wholeheartedly an enlightened art criticism may embrace a phenomenological approach,

it must fall silent on the topic of images that weep, bleed, sweat, or blink. Emotional response to sculpture as if it

were alive unacceptably crosses the line from aesthetics — a branch of philosophy — to religion, where logic

stands on less sure footing. This is a final, crucial reason why Spanish polychrome figure sculpture had to be ignored and

overlooked in the study of art, and why its characteristic features (paint, clothing, wigs) continue to be dismissed as fatalistic,

essentialist, reactionary kitsch: It threatens to expose what got left behind when the canons of taste and the discipline

of art criticism were being established — in short, the artifact as magic, and the artist as shaman.

ART CRITICISM AROSE during the Enlightenment "as something independent of specific uses, ... a field of study for those who

had never touched either a brush or a chisel" (Bluhm 14). As part of the Age of Reason project of "partitioning the sensible"

(as Jacques Ranciere terms it) to valorize secular over mystical truth, the rationalization of art manifested on the canvas

and in the workshop as a formalist prejudice for white marble, clarity of contour, truth to materials — in short, a

conformity to discipline that would represent a triumph of reason over sensation and belief (Bluhm 15). Baroque style, which

by the late 17th century already was installing timeless, frozen, heroic subjects to replace the immediacy of Counter-Reformation

goals, took a decisive turn toward Neoclassicism in the 18th century, leaving behind scores of bloody Judith and Holofernes

beheadings, arrow-riddled Saint Sebastians and the entire catalogue of Spanish polychrome figure sculpture. In fact,

Spanish critics had been writing themselves out of the art canon as soon as they tried to join the conversation, betraying

their emotions when it came to their hometown icons (McKim-Smith 15-18). Antonio Palomino, an early Spanish critic, said of

Luisa Roldán's Jesus of Nazareth:

"I was so thunderstruck at its sight that it seemed irreverent not to be on my knees to look at it, for it really appeared

to be the original itself.... The respect and reverence that it produced was such that I swear I lack the words to manifest

it! For not only the head and facial expression..., but the hands and feet were so marvelously executed (and with some drops

of blood trickling down) that everything looked like life itself" (qtd. in McKim-Smith 16).

Sixteenth-century commissions for processional sculpture explicitly called for works that looked "alive," while testimonials

revert to stock praise for images "'so alive' that the 'hearts' of onlookers were moved, and they responded with 'devotion'

and 'piety'" (Webster 173).

Such language clearly violates the "disinterested attitude" that is a condition of aesthetic judgment as codified by Immanuel

Kant. As McKim-Smith says, "philosophical praxis has demanded that to be canonical, a sculpture's value must be exclusively

aesthetic, not religious or animistic; aesthetics and religion belong to categories that are ontologically extinct" (23-4).

Yet Spain's first surviving treatise on art stated plainly in 1649 that "sculpture has existence and painting has appearance"

(qtd. in Webster 57). In the context of the Holy Week project to invert or "transform temporarily the relationship between

image and audience," the image becomes real and can look back at the spectator (Webster 163). Indeed, realistic figure

sculpture, through its ability to mimic life and "fool" us, challenges our identity as distinct from the non-living, for "[i]t

is the particular perspective of human subjectivity that allows the statue that is 'unlike' ... to seem 'like'" (Camille

36). Simulacra and doubles thereby make felt the tenuous, subjective ground of identity.

To conclude, while it adheres in structure to biblical narrative and church doctrine, Holy Week in its facticity — the

mass worship of dolls as if they were alive — represents a communal will to experience the origins of the sacred, which

I would formulate as trauma of separation from the mother, writ large. The Oedipal moment, so central to the psychoanalytic

account of individual becoming, is instantiated here as the source of cultural creation, in an ironic contravention of the

patriarchal (biblical) understanding of creativity as the province of the father, the "Word made flesh." "Fear of the archaic

mother turns out to be essentially fear of her generative power," Kristeva writes (Powers 77); and it is to the mother

that the auratic art of the cult object insistently points as the source of raw material for the creative acts of thinking

and knowing.

It is only through the "cult of the mother," Kristeva maintains, that one can navigate the religion of the Word — through

literature and art, the way of "those who make up for the vertigo of language weakness with the oversaturation of sign systems"

("Stabat" 324). Artistic practices signal the preverbal terrain of the "semiotic" as the precondition of the symbolic, just

as the abject both demarcates and threatens to engulf the speaking self. Indeed, much of what was recast in Romanticism as

mystical access by the lone, visionary artist — a trope that persists in the modern era — appears to be what Raymond

Williams calls a residual: a cultural formation that had to be quarantined off as part of the process of establishing the

dominant (121-7). We could say that Spanish processional sculpture here represents the "abject" of European art history, against

which it disclaimed the Baroque and its more problematic aspects, especially those that transgress the boundaries between

the artwork and the viewer. By the time mystical knowledge re-emerges in Modernist formulations of universal essence, it has

been safely abstracted into an ideological, formal concern at several removes from the immediately personal — the artwork

can no longer, in any way, be thought of as a psychic "parent."

What remains of the "soul" of art — what Walter Benjamin called its aura (217-52) — is inverted by Postmodern

art to reveal the ubiquitous commodity, an elaboration of exchange values already present in the conceits of 18th-century

private easel painting (Berger 83-112). While it is common today for products in advertisements to move, talk, think, and

claim the power to transform us, the magical aspect of actual objects has become unthinkable. We are meant to understand that

an object's power is conferred through purchase — the currency is money, not emotion — and this extends equally

to the objects classified as art. The fact that Spanish processional sculpture still cannot be classified as art goes hand

in hand with its resistance to being sold, exchanged, or displayed as part of a nation's cultural inventory; for its power

is experienced as actual and immediate, rather than abstract and timeless (Webster 98). To participate in this work is to

share Jean-Paul Sartre's category-crumbling experience that "during emotion it is the body which, directed by the consciousness,

changes its relationship with the world so that the world should change its qualities" (qtd. in Mitchell 16).

With the loss of efficacious emotion, the sanctity of violence, and the magical object, modern man remains cut off from his

source. Although he admits of transgressive urges, Bataille says, he classifies them as pathology, where they are much more

readily admitted than as an integral aspect of spirituality (182-4). Eroticism thus remains the paramount problem for humans,

individually and universally, according to Bataille, which reason cannot address (259). For philosophy cannot escape the limits

of language; "it uses language in such a way that silence never follows, so that the supreme moment is necessarily beyond

philosophical questioning.... [t]he supreme questioning ... to which the answer is the supreme moment of eroticism" (275).

And it is to this moment of violence, tears, and transcendence that the Spaniards' suspension of aesthetic discipline perilously

returns us.

WORKS CITED

Bataille, Georges. 1962. Death and sensuality. New York: Walker & Co.

Benjamin, Walter. 1968. "The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction." Illuminations. Ed. Hannah Arendt.

New York: Schocken Books. 217-52.

Berger, John. 1977. Ways of seeing. London: Penguin Books. 83-112.

Bluhm, Andreas. 1996. "In living colour: A short history of colour in sculpture in the 19th century." The colour of sculpture,

1840-1910. Catalog of the exhibition, Van Gogh Museum and Henry Moore Institute, Leeds.

Camille, Michael. 2003. "Simulacrum." Robert S. Nelson and Richard Shiff, Critical terms for art history, 2nd ed. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press. 35-48.

Freud, Sigmund. 2003. The uncanny. Trans. David McClintock. New York: Penguin Books. 121-62.

Grimwood, Steve. 2002. "Beyond the four loves." Theology and sexuality 9(1): 87-109.

Kasl, Ronda. "Painters, polychromy and the perfection of images." Spanish polychrome sculpture 1500-1800 in United States

collections. Catalog of exhibition ed. Suzanne L. Stratton. New York: The Spanish Institute. 33-53.

Kristeva, Julia. 2002. "Stabat Mater." The portable Kristeva. Ed. Kelly Oliver. New York: Columbia University Press.

310-33.

__________. 1982. Powers of Horror. New York: Columbia University Press.

McKim-Smith, Gridley. 1994. "Spanish polychrome sculpture and its critical misfortunes." Spanish polychrome sculpture 1500-1800.

13-32.

Mitchell, Timothy. 1990. Passional culture: Emotion, religion, and society in southern Spain. Philadelphia: University

of Pennsylvania Press.

Payne, Stanley G. 1984. Spanish Catholicism: An historical overview. Madison, Wisc.: University of Wisconsin Press.

Rawlings, Helen. 2002. Church, religion and society in early modern Spain. New York: Palgrave.

Scarry, Elaine. 1985. The body in pain. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Simms, Eva-Marie. 1996. "Uncanny doll: Images of death in Rilke and Freud." New literary history 27(4): 663-77.

Stoichita, Victor I. 1995. Visionary experience in the Golden Age of Spanish art. London: Reaktion Books.

Stratton, Suzanne L. "Foreword." Spanish polychrome sculpture 1500-1800. 5-6.

Webster, Susan Verdi. 1998. Art and ritual in Golden Age Spain. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Williams, Raymond. "Structures of feeling," 128-35, and "Dominant, residual and emergent," 121-7. Marxism and literature.

Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1977. 128-35.

Wittkower, Rudolf. 1999. "Gianlorenzo Bernini (1598-1680)." Art and architecture in Italy 1600-1750. Vol 2: High Baroque.

New Haven and London: Yale University Press. 6-21.

|

|

| Spanish processional pieta, 1725, Los Angeles County Museum of Art |

|

| Semana Santa, Seville |

|

| Nuestra Senora de los Doloros, image belonging to la Hermandad del Santo Entierro, Lanjaron, Grenada |

|

| Gianlorenzo Bernini, Ecstasy of St. Teresa, 1645-52 |

|

| Gregorio Fernandez, Cristo yacente, early 1600s |

|

| Image belonging to Hermandad Hospitalaria y Cofradia de Nazarenos, Bollulos par del Condado, Huelva |

|

| Image of unidentified brotherhood, Barrio Santa Cruz, Seville |

|

| Juan Martinez Montanes, Jesus de la Pasion, early 1600s |

|

| Artemesia Gentileschi, Judith Slaying Holofernes (1614-20) |

|