Paula Nixon

TWO THOUSAND MILES from the small population of Mexican Gray Wolves trying to make a comeback in the mountains of New Mexico and Arizona, a 10-year old boy and an Arctic Gray Wolf are working to help save these endangered wolves native to the Southwest.

Turner Burns just finished the fourth grade. Like many kids, he is spending his summer vacation riding his bike and playing with his dog. What makes Turner a little different from other kids is that he puts a fair amount of time into posting to a Facebook page he created to help raise awareness about wolves.

It all started when his mom asked him if he wanted to go check out some wolves. “Yes!” was his enthusiastic reply—Turner told me he had always wanted to see a real wolf. So they made the four-hour drive from Philadelphia, where they live, to the Wolf Conservation Center (WCC) in New Salem, N.Y.

Seeing the wolves up close in person made Turner realize “how cool wolves are . . . and how many things there are to learn about them. I just got totally passionate about them.” He was 7 at the time, and with the help of his mom he started the website Kids for Wolves, followed by a Facebook page with the same name.

The wolf that inspired it all is called Atka, which means “guardian spirit” in Inuit. Turner describes him as “completely white, with gray spots every once in a while.” Atka is WCC’s primary “ambassador” wolf.

Established

as a wolf sanctuary 18 years ago, WCC has expanded its role to include

participating in the Species Survival Plan for the Mexican Gray Wolf,

breeding and maintaining a small population for possible release into

the Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area in the Apache and Gila national

forests here in the Southwest.

Three ambassador wolves are on display at WCC, where visitors can

attend educational programs to learn about the mythology, biology, and

ecology of wolves and meet Atka, Zephyr, and Alawa. The center’s

population of Mexican wolves is kept in a more secluded area, away from

humans, known only by their studbook numbers.

Atka doesn’t give interviews, either. Early in the evening on one of

the WCC’s wolf cameras, he was lying in the grass snoozing but alert to

what was going on around him: birds chattering in the trees, moths

flitting overhead. Suddenly he heard something and stood, threw back his

head and howled. It was then that I got a good look at him: long

slender legs, large paws, rounded ears, and a bushy tail. He howled for a

few minutes, then lay back down and resumed his nap.

The fi rst time he met Atka, Turner howled with him. Atka is less wary

of humans than most wolves, and not only meets visitors to the

sanctuary, but travels to schools, libraries, and nature centers as part

of WCC’s outreach program, “helping people to learn about the

importance of his wild brothers and sisters,” according to their

website.

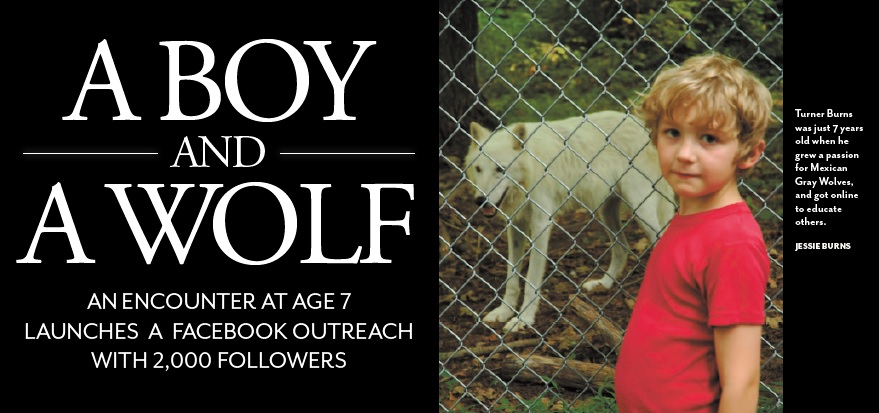

On the Kids for Wolves homepage is a photograph of Turner standing in

front of Atka, separated by the chain-link fence of Atka’s enclosure.

The two share an ability to reach a lot of people with the message that

wolves are an important part of the ecosystem. Last year Atka made more

than 150 outreach visits— and Turner has almost 2,000 followers on

Facebook.

Maybe this year Turner will get his wish—to have Atka visit his school.

Paula

Nixon moved to New Mexico just as endangered Mexican Gray Wolves were

being reintroduced into their historic range, and has been following

their progress ever since. She blogs about wildlife and nature at www.paulanixon.com